Harvard University Electricity Policy Group

The Harvard Electricity Policy Group (HEPG) is run by Ashley Brown, a former commissioner on the Ohio Public Utilities Commission, who has publicly criticized distributed renewable energy repeatedly for months while also providing expert testimony on behalf of utility companies in regulatory hearings. Based at the Mossavar-Rahmani Center for Business and Government at Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government, HEPG has existed since 1993.

Recently, Brown has written journal pieces, including one in the December 2014 issue of publisher Elsevier’s The Electricity Journal. The articles argue that solar advocates overvalue distributed generation and the “value of solar” approach is severely flawed. Elsevier failed to acknowledge the industry funding of HEPG and Brown’s connections as a private consultant to the utility industry. A similar failure occurred when Elsevier published six articles authored by scientist Willie Soon but did not disclose the funding. Soon was paid by Southern Company along with ExxonMobil for research casting doubt on mainstream climate science.

Brown also had an opinion piece published in Utility Dive in March 2015 that concluded:

Rooftop solar is the least-efficient and least cost-effective form of renewable generation, and subsidies to DG solar end up biasing the market against more efficient and cost-effective renewable sources. It is highly likely that overpayments for DG have the effect of squeezing more efficient forms of renewable energy out of energy markets by using preferential pricing to grab a disproportionate share, ultimately driving up the cost of reducing carbon.

Brown has also written to The New York Times after the newspaper’s editorial board published an article titled, “The Koch Attack on Solar Energy.” Brown writes, “What was proposed in Arizona and elsewhere is not a tax, but rather a fairer, less socially regressive distribution of network costs.”

On July 29, 2015, Brown addressed the National Governors Association with a presentation titled, “Protecting Customers and Addressing Cross-Subsidization: Unintended Consequences of Retail Net Metering.” In the presentation, Brown claims there is a “massive wealth transfer to solar installers with no appreciable consumer benefit.”

Finally, in recent testimony in Oklahoma, Brown compared a solar industry-backed group to a parent murderer, saying:

The more net metering for distributed generation continues, the more problematic the inclusion of additional costs within the “energy charge” becomes. For TASC [The Alliance for Solar Choice, a pro-solar organization] to raise this issue is extraordinarily ironic—they once again resemble the patricidal child who pleads for mercy because he is an orphan.

Brown also claims that distributed solar results in a wealth transfer from lower income to higher income groups. But Brown relies on a single study in California showing the median income for a solar system household was approximate $40,000 above the state median and does not actually prove that solar homeowners result in the financial burden for lower-income ratepayers.

Karl Rabago, Executive Director of the Pace Energy and Climate Center, explains in a recent response to Brown’s assertions that the value of distributed solar generation varies depending on where and when the electricity is generated. By claiming that the wholesale cost of utility scale solar is more efficient, Brown ignores multiple factors that affect the value of distributed solar, including the distribution cost. Rabago asserts that Brown’s claims are simply not supported by data and that Brown fails to counter studies conducted in Maine, Minnesota, Austin, and elsewhere that show retail rate credits undervalue the benefit of distributed solar generation.

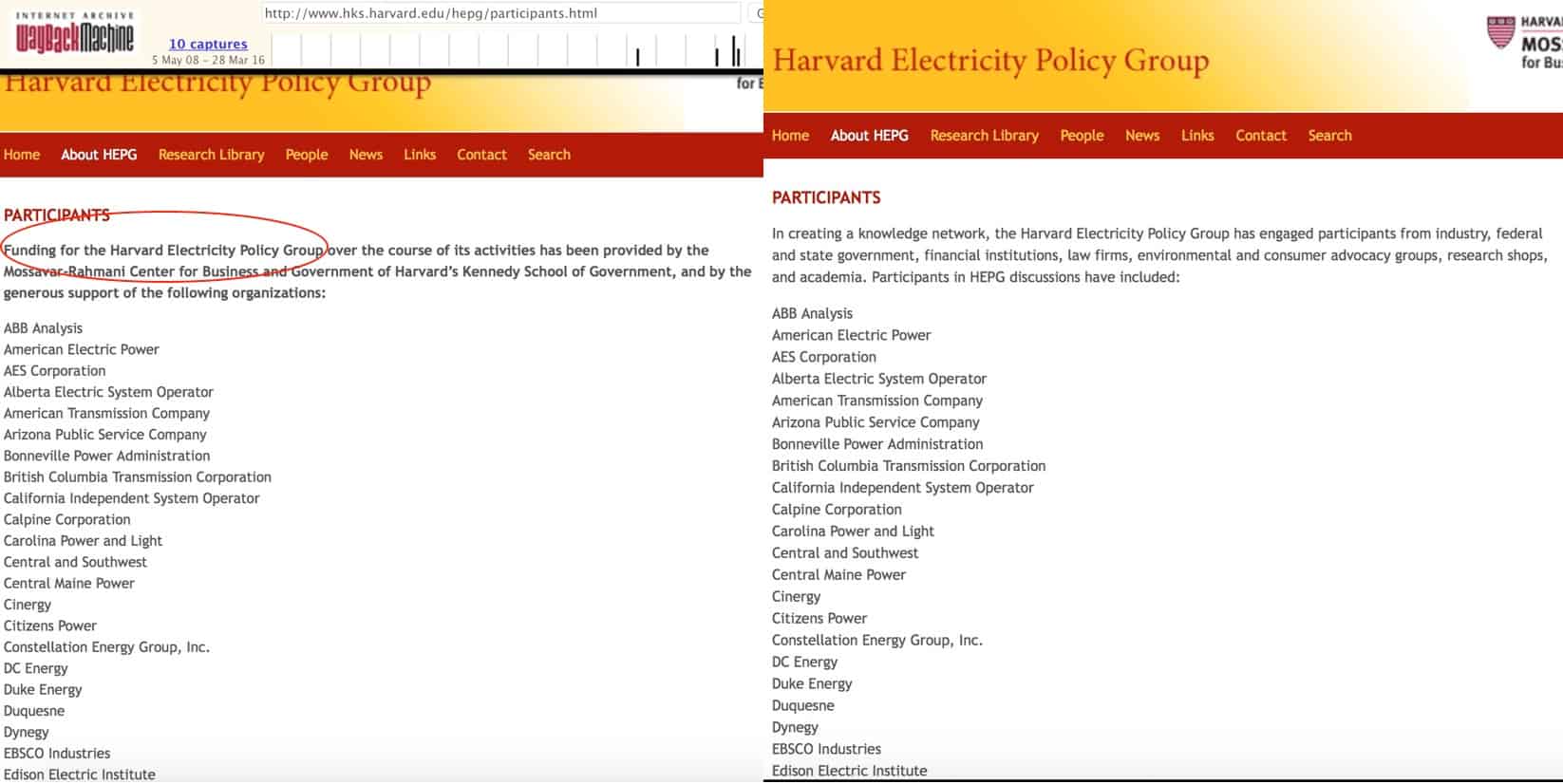

As of March 2016, HEPG stated on its website that it is funded by “the generous support of the following organizations,” and then lists 79 entities. Below are some of the companies listed as funders of HEPG that have a direct stake in preventing distributed generation from continuing to expand in the marketplace:

- American Electric Power

- Arizona Public Service

- AES Corporation

- Duke Energy

- Dynegy

- Edison Electric Institute

- Exelon

- FirstEnergy Corporation

- National Grid

- National Rural Electric Coop

- PacifiCorp

- Pacific Gas and Electric

- Southern Company

- Tucson Electric Power

- WEC Energy Group

- Wisconsin Public Power

- Xcel Energy

HEPG’s website detailing the funding from utility companies, trade associations, and law firms were recently deleted and changed to read, “Harvard Electricity Policy Group has engaged participants from industry, federal and state government, financial institutions, law firms, environmental and consumer advocacy groups, research shops, and academia. Participants in HEPG discussions have included.”

None of the funding from the companies is disclosed in the aforementioned articles authored by Brown. Readers and viewers are only told that he is affiliated with Harvard University, despite his organization’s funding and his personal contracts with utility companies to submit testimony on their behalf in regulatory hearings across the country.