U.S. DOE: Magical Thinking on Future Shale Gas Supplies

The U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE’s) Energy Information Administration (EIA) is the go-to source for data on electricity, natural gas, petroleum, nuclear, coal, emissions, energy efficiency and renewable energy. Every year, the EIA publishes its Annual Energy Outlook (AEO), which includes both historical data and future forecasts, including for our supply of shale gas.

Why is this important? Because the EIA’s forecasts are used by utilities and analysts, and hundreds of billions of dollars of investment are dependent on the accuracy of those forecasts.

If the EIA’s forecasts of vast amounts of shale gas for the next 30 years are inaccurate, the public is in for a rude awakening because there will potentially be billions of dollars in stranded natural gas pipeline and power plant assets.

Not everyone has drunk the Kool-Aid of ever-increasing natural gas supplies. Canadian geoscientist David Hughes and Houston-based geological consultant Art Berman have held contrarian positions on shale gas supplies for many years.

Hughes says shale gas supplies are vastly overstated, while Berman says that current natural gas prices are not enough to pay for the cost of production; and without cheap credit, the shale boom would never have happened.

Hughes has produced a series of studies on these reports for nearly a decade. He has studied energy resources for four decades, spending 32 years with the Geological Survey of Canada as a scientist and research manager. He developed Canada’s National Coal Inventory to determine availability and environmental constraints. Berman has worked as an independent energy industry consultant for two decades, and before that, he was with Amoco Corporation (now BP) for twenty years. He holds an M.S. in Geology.

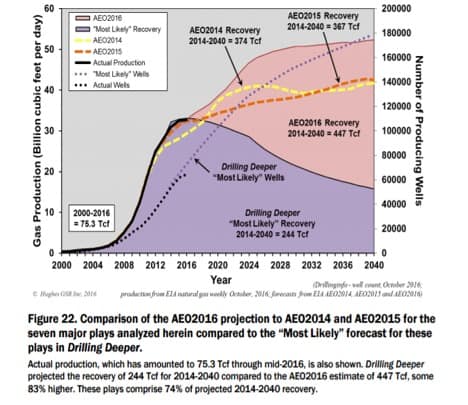

What Hughes witnessed had him scratching his head since the EIA considerably increased its projections for total U.S. shale gas production from the AEO 2015 to AEO 2016, for no apparent reason.

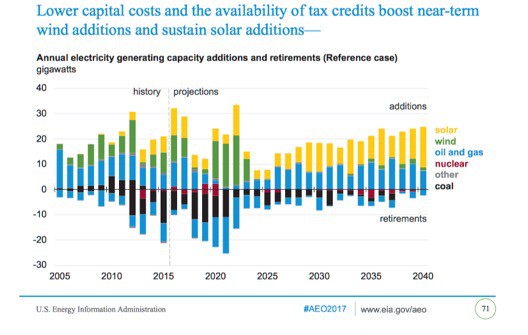

Since 2009, FERC has approved 5,000 miles of pipelines, with an additional 3,500 miles in the process. According to Bloomberg, these pipelines represent a $35 billion investment. This investment dwarfed by the staggering number of natural gas-fired power plants that have been built in the past 17 years – and the huge number of gas plants in the pipeline. An estimated 284,000 MW of natural gas power plants were added to the U.S. grid from 2000 to 2015, and there’s another 140-150 GW of gas that’s expected to be built between 2015 and 2040, per the EIA’s AEO 2017.

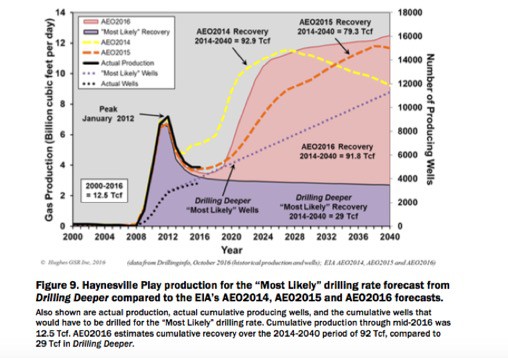

The EIA is counting on an ever-growing source of natural gas, and Hughes unpacks the changes between AEO’s 2014, 2015 and 2016 estimates below. While EIA estimated recoverable gas at 367 tcf in 2015, EIA increased that to 447 tcf in 2016.

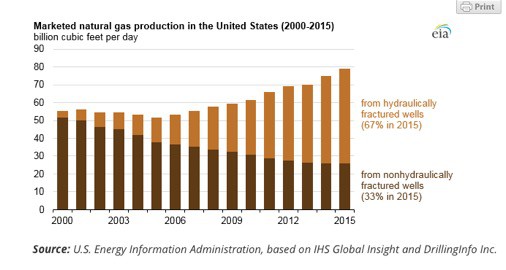

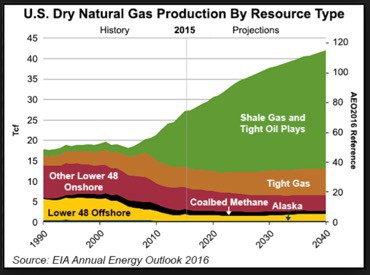

Why is shale gas production so important? Because 67% of total U.S. natural gas now comes from hydraulically fractured wells, up from only 7% in 2000. The number of fracked wells also increased dramatically, from 26,000 to an estimated 300,000. While the production of fracked gas has increased, the production of ‘conventional’ gas, i.e. gas drilled in vertical wells, has decreased from 93% to 33%.

Where will the additional gas come from? According to EIA’s magical thinking, the increase will come from plays like the Haynesville, which is currently down by half; EIA expects it to make a comeback and produce twice the amount of gas that it produced at its January 2012 peak.

The graph below shows the EIA’s 2016 estimate of future natural gas supplies out to 2040. And the EIA’s 2017 estimate reports even more natural production, increasing out to 2050 and beyond.

To say the least, utilities and pipeline companies around the U.S. have a lot riding on shale gas. This is more than an academic question, as many as tens of billions of dollars are bet right now on assets that could be stranded.