Pollution Payday: Analysis of executive compensation and incentives of the largest U.S. investor-owned utilities

While the coronavirus pandemic has devastated the U.S. economy, leaving millions of Americans struggling to afford their utility bills, the top executives for those utilities continue breaking their own records for executive compensation every year.

The Energy and Policy Institute analyzed the executive compensation policies and practices of 19 of the largest investor-owned electric utilities throughout the United States. In addition to identifying trends across utilities, this report provides company-level profiles on the executive compensation policies of each of the utilities included in our research.

Download our entire report (.pdf) here.

Click to jump to the utility profiles.

We found that CEO compensation at these 19 companies totaled over $764 million between 2017 and 2019, with the highest-paid CEO in the group, Southern Company’s Thomas A. Fanning, receiving nearly $28 million in 2019. The ratio of Duke Energy CEO Lynn J. Good’s pay to that of an average employee of her company reached 175:1 in 2017 – the highest of any utility for a single year in the same three-year period.

Investor-owned utilities have argued publicly and to policymakers that they must continue disconnecting customers who have been unable to pay their electric or gas bills. If they don’t have the threat of disconnections, the companies say, they will have to raise rates on other customers to cover the arrearages of those who can’t pay.

But the data in this report show that investor-owned utilities have large pots of executive compensation from which they can draw before turning to rate increases. If Southern Company’s Fanning took just a 32% compensation cut from his 2019 amount – still leaving him with a compensation of $19 million – Southern could use the savings to immediately wipe out the debt of every single Georgia Power customer that was over 90 days in arrears on their bills as of the end of July 2020. Instead, Georgia Power disconnected 13,000 customers in July, starting when regulators allowed a state moratorium on disconnections to expire on July 14. (Of course, Southern could also choose to avoid both disconnecting customers and rate increase requests by tapping into a small percentage of the billions of dollars in corporate profits that it netted in 2019.)

Out-of-control executive pay is not unique to the utility sector. Theories of corporate compensation as “rent extraction” – enriching executives, rather than producing shareholder value – have gained traction, advanced by scholars like Lucian Arye Bebchuk and Jesse M. Fried, as income inequality has skyrocketed in America. But executive compensation at investor-owned utilities deserves extra attention for several reasons.

First, governments have granted monopoly status to investor-owned electricity and gas utilities, which means that families and businesses often have no choice but to fund the exorbitant salaries and perks of their utilities’ executives. In some cases documented in this report, utilities have tried to recover the costs of their executive compensation directly from ratepayers’ bills, rather than from shareholder profits. We found that utility executives took home bloated incentive awards, routinely receiving stock shares for performance that doubled company targets. These excesses have prompted utility consumer advocates and some state regulators to oppose saddling ratepayers with the steep costs of executive pay.

Second, the choices made by investor-owned utilities’ executives will be pivotal in whether the United States rapidly decarbonizes its economy. With just a single notable exception of Xcel Energy, the executive compensation policies of the utilities we studied in this report do not incentivize decarbonization. In some cases, we found that executive incentives are directly at odds with reducing emissions by transitioning away from fossil fuels. Some utilities include environmental, social, or governance (“ESG”) goals in their executive incentives that do nothing to promote decarbonization, despite the fact that climate change is a key area of focus for ESG-oriented investors.

A growing number of investors expect companies to link executive compensation to decarbonization goals. In September 2020, major investors with over $47 trillion in assets informed CEOs and directors of several utilities that “companies will be assessed on progress made in becoming net-zero businesses,” including “Whether the company has effective board oversight of, and remuneration linked to, delivery of GHG [greenhouse gas] targets and goals.”

Several of the utilities we studied also use misleading financial metrics as a basis for determining executive compensation, inflating resultant payouts to corporate officers. These tactics include employing non-standard accounting measures and manipulating inappropriate company peer groups for comparison.

Finally, we examined some of the lavish perquisites (or “perks”) doled out to utility executives, such as unlimited personal travel on corporate aircraft, expensive legal and financial services, and a host of “personal benefits” – quickly amounting to further exorbitant tallies.

The primary source of data for this report is utilities’ own annual financial disclosures, namely their 2018 through 2020 “proxy filings”, also known as Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) Form DEF 14A.

Excessive Compensation

CEO compensation for 19 major investor-owned utilities totaled over $764 million from 2017 to 2019. Total CEO compensation for each utility ranged from approximately $20 million to $62 million over the three years.

Annual total CEO compensation for individual utilities ranged from $6.5 million to $27.8 million.

That places utility CEO pay roughly in line with that of executives at the nation’s largest firms more broadly; CEOs of Fortune 500 companies earned an average of $14.8 million in compensation in 2019, according to the AFL-CIO. Unlike executives at other Fortune 500 firms, leaders of investor-owned utilities do not have to navigate competitive pressures, since they are granted sanctioned monopolies by state governments.

The highest-paid utility CEO during the 2017 to 2019 period was James L. Robo of NextEra Energy, who received more than $62 million in total compensation from 2017 to 2019.

Southern Company CEO Thomas A. Fanning ranked second, collecting over $56 million in total compensation from 2017 to 2019. Fanning also received nearly $28 million in total compensation in 2019 alone, which was the highest compensation for any utility CEO in any single year, and almost $14.8 million more than his compensation the previous year.

Table 1: Compensation for utility chief executive officers, 2017-2019

Utility executive pay continues to increase as customers face disconnection during COVID-19 crisis

Investor-owned utilities have argued publicly and to policymakers that they must continue disconnecting customers who have been unable to pay their electric or gas bills during the COVID-19 crisis. If they don’t have the threat of disconnections, the utilities say, they will have to raise rates on other customers to cover the arrearages of those who can’t pay.

But investor-owned utilities have large pots of executive compensation from which they can draw before turning to rate increases.

If Southern Company’s Fanning took just a 32% compensation cut from his 2019 amount – still leaving him with a compensation of $19 million – Southern could use the savings to immediately wipe out the debt of every single one of the 74,006 Georgia Power customer that was over 90 days in arrears on their bills as of the end of July 2020, according to data the company submitted to Georgia regulators. Instead, Georgia Power disconnected 13,000 customers in July, starting when regulators allowed a state moratorium on disconnections to expire on July 14, 2020.

If NextEra’s Robo took a 50% cut from his 2019 compensation – still allowing him to take home over $10 million – the company could use that money to wipe out the debt of 43,581 Florida Power & Light customers who were in arrears as of the end of June 2020, according to data NextEra submitted to Florida regulators.

Duke Energy CEO Lynn J. Good could take a 50% cut from her 2019 compensation – still earning over $7.5 million – and the company would be able to wipe out the debt of over 28,163 residential Duke Energy customers in the Carolinas who were considered past due on their bills as of July 31, 2020, according to data Duke submitted to North Carolina regulators.

DTE Energy could use half the compensation that it paid former CEO Gerard M. Anderson in 2019 – leaving over $6 million for CEO compensation – and use that to cover the arrearages of 6,768 senior and low-income customers who were 90 or more days late on their payments as of August 16, 2020, according to data DTE submitted to Michigan regulators.

Xcel Energy could use half the compensation that it paid CEO Ben Fowke in 2019 – still leaving nearly $8.5 million for CEO compensation – to cover the arrearages of 23,173 residential gas and electric customers in Minnesota who were late on their payments as of the end of July 2020, according to data Xcel submitted to Minnesota regulators.

Of course, all of these utilities could also choose to avoid both disconnecting customers and rate increase requests by tapping into a small percentage of the billions of dollars in corporate profits that they netted in 2019. As the Virginia Attorney General’s Office commented in the state’s utility disconnection moratorium docket, “for investor-owned utilities, it is possible that utility management could simply share the financial burden with shareholders, as other businesses impacted by the pandemic have had to do.”

CEO “pay ratio” shows wide gap with employee compensation

Investor-owned utilities report annually on their CEO pay ratio, which illustrates the gap between the annual total compensation for a utility’s CEO and average compensation for other employees of the company.

No utilities report on how CEO compensation compared to the median income of the customers they serve.

NextEra Energy reported the highest average CEO pay ratio at 164:1 for 2017 to 2019.

Duke Energy ranked second, with a 139:1 average CEO pay ratio between 2017 and 2019. Good also had the highest CEO pay ratio for any single year, at 175:1 for 2017.

For some utilities, the gap in CEO versus median employee compensation increased annually over the three-year period. Southern Company saw the largest increase from 2017 to 2019, with its CEO pay ratio rising 52 points from 114:1 to 166:1.

Other utilities reported their highest CEO pay ratio during the three-year period in 2017 or 2018.

Large swings in the annual CEO pay ratio reported by utilities may be due to changes in CEO compensation, but also to other factors like corporate restructurings.

For example, FirstEnergy reported its highest CEO pay ratio of 115:1 in 2018, a year in which CEO Charles E. Jones received his lowest annual compensation for the three-year period. In 2018, FirstEnergy reported CEO compensation of $11.1 million and median employee compensation of $96,805.

The previous year, in 2017, FirstEnergy reported its highest annual CEO compensation of almost $15.3 million for Jones, but a lower CEO pay ratio of 90:1. The median employee compensation FirstEnergy reported for that year was nearly double, at $170,299.

In 2018, FirstEnergy excluded all employees in its Competitive Energy Services businesses from its median employee compensation analysis due to the “deconsolidation” (i.e. bankruptcy) of its subsidiaries, FirstEnergy Solutions and the FirstEnergy Nuclear Operating Company. Those subsidiaries later emerged as a new company called Energy Harbor, and the median compensation of the employees left at FirstEnergy fell.

Table 2: Pay ratio of utility chief executive officers to the median employee at the company, 2017-2019

Utilities reward executives with 200% maximum payout for performance shares

Performance-vesting stock awards are one example of a long-term incentive common to executive compensation plans.

Performance metrics are measured over a multi-year period, and policies typically allow for a payout to executives of up to 200% of the award for achievements in excess of the target metrics. For instance, in one analysis, 81% of oil and gas companies studied provided for a maximum 200% payout of performance shares in 2018.

Executive compensation plans for all of the utilities we analyzed set a maximum payout for performance shares of 200% of the performance target.

Shareholders approve of utility executive compensation plans

Shareholders for all of the utilities in this report approved executive compensation plans in 2020.

FirstEnergy’s executive compensation plan received the most support from shareholders, with approximately 96.7% approval.

Dominion Energy’s plan received the least support, but still reached 86.6% approval.

Table 3: Shareholder votes on utility executive compensation plans, 2020

Ratepayer recovery of executive compensation questioned at state utility commissions

In 2009, during the Great Recession, the National Association of State Utility Consumer Advocates (NASUCA) raised the alarm about utilities’ executive compensation, and NASUCA encouraged states to limit the amount of executive salaries and benefits that utilities could recover from ratepayers.

The recession and subsequent concerns expressed by consumer advocates got regulators’ attention, threatening utilities’ ability to recover executive compensation from their captive customers. As one utility lawyer from Akin Gump wrote in a 2011 article advising utilities how to avoid regulatory scrutiny, “Any notion that utility executives are insensitive to customers’ interests, or ‘out of touch’ with the economic realities consumers face, must be absolutely avoided and dispelled by the utility in rate case proceedings.”

Eleven years later, as ratepayers face another economic downturn caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, protections to shield them from paying for the lucrative compensation packages of utility executives vary and are lacking in some states.

A survey of twenty-four western states by the Garrett Group, last updated in 2018, found that “a clear majority of the states surveyed follow the financial-performance rule, in which incentive payments associated with financial performance are excluded from rates.”

Some states still allow a portion of short-term incentive compensation to be included in rates, though the Garrett Group survey also found that “none of the jurisdictions surveyed allow full recovery of incentive compensation through rates as a general rule.”

Hawaii regulators have gone a step further and allow no executive incentives to be recovered through rates, according to the survey.

Other states, however, have no such limits. In 2019, the Indiana Utility Regulatory Commission faced a request by Indiana Michigan Power, a subsidiary of American Electric Power (AEP), to include $23.7 million in annual incentive plan costs and $6.98 million in long-term incentive plan costs in rates paid by customers. Mark Garrett of the Garrett Group, on behalf of the Indiana Office of Utility Consumer Counsel, recommended the commission exclude at least half the annual incentive costs and all long-term incentive costs, but the commission sided with the utility in its 2020 order in the case.

In its most recent South Carolina rate case, which concluded in 2019, Duke Energy sought to raise rates on its average residential customer by $14 a month, including a massive increase in fixed fees that the company charges. The state Public Service Commission’s (PSC’s) decision effectively halved Duke’s request, though the utility has since appealed that decrease to the South Carolina Supreme Court.

South Carolina regulators’ objection to the full rate hike included Duke’s proposed recovery of executive compensation costs from ratepayers. In a unanimously-approved PSC directive, Commissioner Thomas Ervin wrote:

“the CEO and executive team demonstrated they were ‘tone deaf’ as to how a 238% increase in the Basic Facilities Charge [fixed fee] would have negatively and adversely impacted the elderly, the disabled, the low income and low use customers. It is one of the reasons I am recommending a 75% disallowance of the CEO’s excessively high executive compensation for South Carolina during test year 2017 and a 50% disallowance for the next three highest Company executives.”

Even where protections exist, some utilities still try to win approval to recover incentives from their customers.

Chattanooga Gas Company, a subsidiary of Southern Company, sought approval for both short-term and long-term incentives for its executives and other high-ranking employees in 2019. The Tennessee Consumer Advocate opposed the company’s proposal. The Tennessee Public Utility Commission ultimately allowed 50% of the short-term incentive to be recovered in rates while rejecting the company’s request for recovery of long-term incentives.

DTE Energy appeared to try to simply ignore Michigan Public Service Commission (PSC) precedent when it requested a rate increase in 2019. Michigan Attorney General (AG) Dana Nessel’s office found in DTE’s request that in addition to including costs for incentive compensation in operations and maintenance accounting, the utility included capitalized costs of short-term and long-term incentive compensation in its rate base projections – meaning it would not only recover the costs of the incentive compensation, but also earn profits on it.

Attorney General witness Sebastian Coppola said DTE’s incentive plans are “too heavily skewed toward measures that directly benefit shareholders as opposed to customers.”

The AG’s Office recommended the PSC remove all capitalized incentive compensation costs associated with financial measures from the rate case.

The Administrative Law Judge in the case (ALJ) not only agreed, but recommended the PSC order DTE to:

“immediately provide the Commission with a report in this docket identifying the amount of incentive compensation attributable to financial measures DTE has included in rate base at least over the last five years, and direct DTE to clearly exclude such amounts from rate base in its next rate application. The Commission may also want to initiate an investigation to determine what faulty managerial or other decision-making process led DTE to flagrantly ignore the Commission’s numerous decisions on this expense category.”

The PSC agreed with the AG and the ALJ, and disallowed $44 million from rates. The regulators said in the order they were “profoundly concerned as to why DTE Electric would think it would be acceptable to capitalize financial-based employee compensation incentives under rate base.” The order further said:

“The fact that DTE Electric booked these incentive compensation costs to rate base without being ‘caught’ by parties or the Commission in prior proceedings does not render them reasonable and prudent now, nor does their removal from rate base for rates being set on a going-forward basis constitute retroactive ratemaking … the Commission has been unwaveringly clear that ‘incentive compensation tied to financial performance measures has not been shown to benefit ratepayers.’” (emphasis added)

In September 2020, Arizona Corporation Commission Chairman Bob Burns filed a letter in Arizona Public Service Company’s rate case seeking answers to 26 questions about the company’s executive compensation of senior executives, as well as the number of senior executives. Burns requested responses from the company as well as commission staff and Arizona’s Residential Utility Consumer Office, explaining:

“It has come to my attention that perhaps the amount of upper level management at Arizona Public Service Company (APS) may be excessive and that the salary level of this upper level management may also be excessive when both levels are compared with other large corporations.“

Misalingment with Decarbonization

While most major investor-owned utilities have established goals to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions, those goals are not yet reflected in the companies’ executive compensation policies. Some utilities’ executive compensation policies encourage renewable energy growth or discourage air and water pollution violations, but only Xcel Energy rewards its executives for the company’s progress toward its decarbonization goals. Some utilities’ executive compensation policies even conflict with their decarbonization goals, as is the case with outdated policies that encourage the operation and availability of coal plants.

The CEOs and Boards of Directors of several electric utilities were put on notice in September 2020 that major investors will assess their companies based in part on whether their executive compensation policies support decarbonization. A group of 500 global investors with over $47 trillion in assets wrote to executives and directors to inform them that “companies will be assessed on progress made in becoming net-zero businesses,” including “Whether the company has effective board oversight of, and remuneration linked to, delivery of GHG targets and goals.”

An exception to the rule: Xcel Energy incentivizes executives to meet targeted greenhouse gas emissions reductions

Xcel Energy’s carbon emissions reduction incentive program is “based on the achievement of a specified reduction in carbon dioxide emissions.” For the three-year period ending in December 2019, the carbon emissions reduction target was a 33% reduction of CO2 emissions from 2005 levels. For the three-year period ending in December 2021, the carbon emission reductions target is a 47% reduction of CO2 emissions from 2005 levels. If Xcel Energy were to reduce its emissions more than the target, executives would receive higher incentives, while a failure to reduce emissions beyond a threshold amount would mean that executives would not receive any incentive. In 2019, Xcel achieved in excess of its company emissions reduction goal, and named executive officers (NEOs) received approximately 127% of the target incentive payout.

Xcel Energy’s carbon emissions reduction incentive program comprises 30% of executives’ long-term incentive, which accounts for approximately 71% of CEO Ben Fowke’s total compensation, and 54% of the average of all other NEOs’ total compensation. In other words, the carbon emission reductions incentive program accounts for about 21% of the CEO’s total compensation, and 16% of all other NEOs’ total compensation. Xcel Energy has established a goal to reduce carbon emissions 80% by 2030 from 2005 levels, and generate 100% carbon-free electricity by 2050.

Some utilities’ executive compensation policies include environmental metrics, but don’t focus on reducing greenhouse gas emissions

Some utilities’ executive compensation policies include environmental metrics, such as encouraging renewable energy development or discouraging air and water pollution violations. But those policies fail to align executives’ compensation with utilities’ decarbonization goals, because they don’t require executives to actually reduce greenhouse gas emissions in order to receive the incentives.

Southern Company’s executive compensation policies include incentives for CEO Thomas A. Fanning if the company adds zero-carbon resources or closes coal plants. The policy is not tied to actual emissions reductions and is silent on gas power plants. Therefore, Fanning could receive the incentive if the company’s greenhouse gas emissions decreased only modestly, or even hypothetically if they increased. The policy applies to only the CEO, and other executives, such as those at Southern’s operating companies like Alabama Power, are not compensated for the addition of zero-carbon resources, closing coal plants, or reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Southern set a goal to be net-zero carbon by 2050, though it continues to invest in new fossil fuel infrastructure and has been vague about how it will “net” its emissions.

American Electric Power (AEP) added a new metric in 2020 to its long-term incentive plan, which will “measure the increase in the Company’s non-emitting generation capacity as a percentage of total generation capacity.” The company defines non-emitting generation as “nuclear, hydro, wind, solar, demand-side management and storage,” and said that the new measure “was chosen to align with the Company’s strategy to commit substantial investments that reduce greenhouse gas emissions.” However, during a March 2020 investor presentation AEP said that it plans to add 1,607 MW of new gas power plants to its generation mix over the next ten years.

Duke Energy’s 2020 proxy statement says, “To promote clean energy initiatives, we incorporate a nuclear reliability objective and a renewables availability metric in our STI [short-term incentive] plan to measure the efficiency of our nuclear and renewable generation assets.” Instead of measuring emissions reductions or even renewable energy growth, Duke’s renewables availability metric is “calculated by comparing actual generation to expected generation based on the wind speed measured at the turbine and by calculating the actual generation to expected generation based on solar intensity measures at the panels.” Unlike compensation policies that focus on GHG reductions, incentivizing renewables availability does not encourage executives to move the utility toward a cleaner power supply or reduce emissions. This is the case despite Duke’s stated goal of net-zero carbon emissions by 2050, with an interim goal of a 50% reduction by 2030.

Dominion Energy’s proxy statement refers to a vague “company-wide environmental goal” as well as “business segment environmental goals,” but does not explain those goals. The statement also notes that Dominion CEO Thomas F. Farrell, II “did not have business segment environmental goals.” (On July 31, 2020, Dominion announced changes to its leadership team. Effective October 1, 2020, Farrell will become Executive Chair, and Robert M. Blue, Executive Vice President and co-Chief Operating Officer, will succeed him as CEO.) This is the case despite Dominion’s stated goal of net-zero carbon and methane emissions by 2050, with additional interim goals for cutting its methane emissions.

FirstEnergy’s proxy statement says that “a portion of our annual incentive cash program is tied to ESG (Environmental, Social & Governance) related goals, including Diversity & Inclusion, environmental and safety.” However, the company’s executive compensation policies do not consider greenhouse gas emissions reductions; instead the environmental metrics are focused on “issues related to air emissions, water discharges or other unauthorized releases from facilities that exceed the allowable limitations, conditions or deadlines established in the facilities’ environmental permits.” In other words, FirstEnergy’s plan pays executives bonuses as long as they manage not to break anti-pollution laws.

Alliant Energy’s executive compensation policies include a metric that measures “Annual Progress Towards Long-Term Emission Goal.” A “long-term emissions goal” would lead many investors to assume that the goal refers to greenhouse gas reductions, given the focus on decarbonization in the sector, including the company’s own net-zero by 2050 commitment. But a company spokesperson told the Energy and Policy Institute that the policy refers to other pollutants, such as nitrogen oxides, sulfur oxides, and mercury – not greenhouse gas emissions.

Eversource includes “clean energy execution” as a metric in its executive compensation policy, and says that the company exceeded its 2019 goals through its energy efficiency programs and “[s]ignificant progress with energy storage and electric vehicle projects.” Eversource also established a sustainability goal in 2019 “to be in the 75th percentile of a peer group of comparably sized U.S. utilities whose ESG performance is assessed by the two leading sustainability rating firms,” which the company also determined it had exceeded. Neither the “clean energy execution” nor sustainability metrics appear to measure Eversource’s progress towards its goal to be carbon-neutral by 2030.

The executive compensation policies of Con Edison and PSEG likewise mention renewable energy growth as components of broader goals, but do not reward executives for reducing greenhouse gas emissions. The executive compensation policies of CMS Energy, Entergy, Exelon, NextEra Energy, PPL, and WEC Energy also do not incentivize decarbonization, despite CMS’ goal of net-zero carbon emissions by 2040, and WEC’s of net carbon neutrality by 2050.

Table 4: Utilities with net-zero or carbon-neutral goals have compensation plans that do not incentivize progress toward those goals; some plans conflict with goals outright

| Utility | Decarbonization goal | Executive compensation plan’s relationship to decarbonization |

|---|---|---|

| Xcel Energy | Zero-carbon by 2050 | Incentivizes decarbonization |

| Alliant Energy | Net-zero carbon by 2050 | Does not incentivize decarbonization |

| CMS Energy (Consumers Energy) | Net-zero carbon by 2040 | Does not incentivize decarbonization |

| Dominion Energy | Net-zero carbon by 2050 | Does not incentivize decarbonization |

| Duke Energy | Net-zero carbon by 2050 | Does not incentivize decarbonization |

| Eversource | Carbon-neutral by 2030 | Does not incentivize decarbonization |

| Southern Company | Net-zero carbon by 2050 | Does not incentivize decarbonization |

| WEC Energy | Net carbon neutral by 2050 | Does not incentivize decarbonization |

| Arizona Public Service Company (Pinnacle West) | Eliminate fossil fuels, 100% clean energy by 2050 | Conflicts with decarbonization |

| DTE Energy | Net-zero carbon by 2050 | Conflicts with decarbonization |

Some utilities’ executive compensation policies conflict with decarbonization goals

Some utilities’ executive compensation policies include incentives that conflict with decarbonization goals, such as outdated policies that encourage the operation and availability of coal plants. One utility recently eliminated a policy that encouraged executives to maximize the availability of its coal fleet in response to concerns raised by the Sierra Club.

Arizona Public Service Company’s (APS) executive compensation policy includes incentives based on “[t]he Company’s percentile ranking based on coal capacity factor relative to other companies reported in the Market Intelligence data.” Including coal capacity factors in executive compensation policies conflicts with the company’s goals to eliminate all fossil fuels and achieve 100% clean energy by 2050, because it incentivizes executives to run coal plants even when cleaner and cheaper resources may be available. Another portion of APS’ executive compensation policy includes the “Summertime Equivalent Availability Factor” for each power plant, which measures how much of the year APS’ coal plants are available to operate.

DTE Energy’s executive compensation policy includes a metric for “Fossil Power Plant Reliability,” which is measured by how often its Monroe and Belle River coal plants are “not capable of reaching 100% capacity, excluding planned outages.” The coal-plant reliability metric incentivizes the utility to maintain, at ratepayer cost, coal plants it should be slating for accelerated closure in order to save customers money and achieve the company’s 2030 and 2050 carbon emission reduction goals.

Ameren set a goal in late 2017 of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 80% by 2050 from a 2005 baseline, and to invest in 700 MW of wind and 100 MW of solar power. In 2018, the Sierra Club filed a shareholder resolution protesting Ameren’s continued use of a coal availability metric in its executive incentive structure, to be considered at the 2019 Ameren annual shareholder meeting. Andy Knott, a senior representative for the Sierra Club’s Beyond Coal campaign, told Midwest Energy News that they found the incentive “extremely hypocritical” after Ameren had announced its greenhouse gas reduction goal.

The Sierra Club withdrew the proposal after Ameren agreed to assess the “feasibility of integrating metrics for the reduction of the company’s carbon output, while removing the coal-fired generation availability metric.” In 2019, Ameren’s Board of Directors Human Resources Committee eliminated the coal metric from the short-term incentive program, and added a long-term incentive that will measure the company’s progress towards renewable generation and energy storage additions; both will be effective for 2020. However, Ameren has not released the specifics of how it will incentivize renewable energy and energy storage additions, and Ameren has not said that it will introduce an executive incentive to directly reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Misleading Financial Metrics

Several of the utilities examined in this report are using misleading or problematic financial metrics to calculate executive compensation, often resulting in a greater windfall for executives. Those companies employ two main practices: using non-standard accounting measures, and benchmarking pay to that of executives at inappropriate peer comparison companies.

Utilities use non-standard accounting, boosting executive pay

Many of the utilities we analyzed calculated adjusted earnings based on non-GAAP (Generally Accepted Accounting Principles) metrics, which allowed them to exclude certain items that negatively affected their bottom lines. While a corporate accounting practice not exclusive to utility companies, such exclusions tend to inflate the earnings picture, ultimately resulting in higher incentive-based executive compensation. Exclusions included “extraordinary” or non-recurring events such as plant closures, costs due to regulatory decisions, legal expenses and taxes, and impacts of granting preferred stock and related dividends – all events that are part of the course of business for utilities and for which executive leadership might bear responsibility.

Eversource excluded the failed Northern Pass Transmission (NPT) Project when it awarded its executives compensation in excess of the company’s 2019 performance targets. The utility pulled the plug on the NPT – a transmission line to bring hydropower from Canada to New England – after the New Hampshire Supreme Court sided with regulators’ rejection of the project, leading Eversource to write off $204 million dollars. This exclusion boosted Eversource’s earnings per share (EPS), which is a determinant of pay awarded under its annual executive incentive program. Using this non-GAAP measure, the company’s EPS jumped to $3.45, a $0.64 increase over a standard GAAP calculation. As a result, executives received compensation in excess of the company’s financial performance goals. Eversource also excluded the NPT Project when calculating performance share awards as part of its long-term executive incentive program. While NPT had been on the table since 2010, current CEO James J. Judge – who took over the role in 2016 – continued pushing for the project until its ultimate demise.

When American Electric Power (AEP) awarded its executives’ 2019 performance-based pay, it employed non-GAAP measures to exclude expensing of previously retired coal generation assets in Virginia and the closing of its Conesville coal plant in Ohio. The upshot for its executives amounted to a $4.24 operating EPS, a $0.35 increase over a standard GAAP calculation. The operating EPS is a substantial portion of the company’s compensation plan, consisting of 70% of the annual incentives and a significant part of the long-term incentive plan.

There are exceptions where using non-GAAP accounting in determining executive compensation may have benefits for customers. It may make sense for utilities to use non-GAAP measures to avoid a compensation penalty that could discourage executives from deciding to retire or abandon fossil fuel assets, or other projects that harm customers or provide no benefit, as in the example of AEP’s exclusion of the effect of coal generation retirement on EPS.

Earnest, robust incentives that align compensation with decarbonization goals (see “Misalignment with Decarbonization”) would also help to neutralize any penalties that executives might face from retiring or abandoning fossil fuel assets, and to discourage them from investing capital in those projects in the first place.

FirstEnergy likewise excluded several “special items” from 2019 performance calculations like non-GAAP operating earnings and EPS, including “exit of competitive generation” through its ill-fated subsidiary FirstEnergy Solutions, which emerged from bankruptcy in 2020 as a new separate company called Energy Harbor. This exclusion served as a basis for calculating executive compensation, yielding a non-GAAP EPS of $2.58 that was significantly higher than the $1.70 standard GAAP calculation. Non-GAAP operating EPS accounted for half of the performance measures used to calculate FirstEnergy’s long-term incentives in 2019. It also constituted 70% of short-term incentive measures for the CEO and 50 to 60% for other named executive officers (NEOs).

PSEG excluded “plant retirements and dispositions” as “one-time items” in calculating its 2019 executive compensation. While its use of non-GAAP metrics created a $0.05 decrease in EPS compared with GAAP metrics, the company rewarded executives additionally based upon adjusted operating earnings for its various business units (these are “adjusted for variances between actual interest expense and the business plan”), a metric several of its executives met at the maximum payout in 2019. The company used non-GAAP measures for those incentives, it explained, “because we believe they better reflect operating performance and more directly relate to ongoing operations of the businesses.”

In other instances, utilities exclude costs from their compensation calculations that they incurred due to unfavorable decisions by regulatory or legal bodies.When determining the compensation for former CEO Donald E. Brandt and its other top executives in 2019, Arizona Public Service’s (APS’) parent company Pinnacle West excluded a reduction in APS’ earnings after the Arizona Corporation Commission (ACC) deferred a decision on its cost recovery request to install scrubbers at the Four Corners coal plant. Brandt was CEO when the company decided to install the scrubbers, and his leadership was a focal point during the deterioration of APS’ relationship with the ACC.

In 2019, FirstEnergy excluded from its compensation calculations the “impact” of the Ohio Distribution Modernization Rider, a customer fee rejected that year by the Ohio Supreme Court. While ostensibly billed as a grid modernization charge, opponents assailed the rider as a “blank check” the utility ultimately used to prop up struggling coal and nuclear generation.

Another way utilities inflate executive pay is by excluding various legal expenses, transaction costs, and taxes when calculating compensation. As part of its determinations of EPS and return on equity (ROE) for performance goals from 2017 to 2019, Southern Company excluded legal expenses and tax impacts related to plants under construction. While the company did not name these plants, this reference is likely to its Plant Vogtle nuclear facility in Georgia. Southern Company added that this exclusion included “additional equity return related to the Kemper IGCC [integrated gasification combined cycle] in 2017.” Southern was forced by Mississippi regulators to write off $6.4 billion due to losses of the failed Kemper project.

At the same time, FirstEnergy excluded the impact of tax reform-related refunds to customers that “exceeded budgeted amounts,” as well as the impacts of legal reserves or related expenses.

Both Con Edison’s adjusted earnings for net income for common stock and its adjusted EPS in 2019 excluded transaction costs for its acquisition of Sempra Solar Holdings, LLC.

Utilities have even excluded the expenses associated with granting preferred stock and related dividends. Such is the case with FirstEnergy, which eliminated these costs when calculating its operational earnings for 2019. As Robert Pozen and S.P. Kothari observed in the Harvard Business Review, the Financial Accounting Standards Board has ruled that these expenses should be included in calculating GAAP net income. Accordingly, “it is questionable for a compensation committee to undermine this accounting rule,” Pozen and Kothari wrote.

Utilities levy inappropriate peer company comparisons, increasing executive compensation

One of the common measures utilities employ to calculate executive compensation is comparison to peer companies. The typical corporate compensation committee compares the total shareholder return (TSR) of its own company with those of its peers over the previous three years, as well as the current pay packages for its top executives with those of its peers, according to Pozen and Kothari. Yet constructing inappropriate peer groups alongside which to evaluate utilities opens the door to inflating executive pay.

For instance, a utility may compare itself to a larger and more profitable company by way of adjusting its own revenues. In determining its peer group in 2019, APS announced that it made “certain adjustments to our size measure to account for our operational responsibilities.” These included inflating APS’ revenues by 50% to reflect the company’s “control and responsibility for Palo Verde Generating Station, Four Corners Generating Station and Cholla Power Plant” – an increase of $1.8 billion above the utility’s actual revenues.

In an attempt to justify this practice, APS’ parent company, Pinnacle West, pointed to the increased regulation and complexity of operating the largest nuclear plant in the U.S., Palo Verde. However, operating nuclear projects – even sizable ones – is within the bounds of normal utility business operations, including among other companies discussed in this report. Moreover, Pinnacle West’s claim does not explain why APS counts all of the revenues from the two aforementioned coal plants it operates and co-owns with other utilities. In part because of the resulting inflation of its revenues, APS’ peer group includes some utilities that are much larger, including Southern Company. Southern Company’s market cap – $57 billion as of August 2020 – is more than six times that of Pinnacle West, $9 billion. Peer group comparison is a significant factor determining APS’ executive compensation. The company used this metric to calculate 50% of the pay for two of its executives, and one-third of the pay for its other executives.

Similarly, FirstEnergy packed its 2019 peer group with larger enterprises – including 22 utilities and 44 “general industry” companies from other sectors. Thanks to this comparison, management awarded certain NEOs an increase in compensation “to continue to align with the Blended Median, in the aggregate (within the 85% to 120% competitive range)”.

FirstEnergy’s net income was $908 million in 2019. Yet companies in its “general industry” peer group serving to benchmark its executives’ compensation include the following – all of which earned hundreds of millions, and sometimes billions, of dollars more in income, and whose CEOs made millions more than FirstEnergy’s CEO:

Table 5: Companies in FirstEnergy’s “general industry” peer group skew its executive compensation

| Company | Net income, 2019 | Total CEO compensation, 2019 |

|---|---|---|

| FirstEnergy | $908 million | $14.7 million |

| Honeywell International | $6.1 billion | $18.9 million |

| Raytheon Technologies | $5.9 billion | $21.5 million |

| Eli Lilly & Co. | $4.6 billion | $21.2 million |

| Qualcomm | $4.3 billion | $23 million |

| CSX | $3.3 billion | $15.5 million |

| Norfolk Southern | $2.7 billion | $16.6 million |

| Illinois Tool Works | $2.5 billion | $15.4 million |

| Northrop Grumman | $2.2 billion | $20.3 million |

| Ecolab | $1.5 billion | $19.8 million |

None of these companies include FirstEnergy in their own peer groups to determine compensation. Exelon also includes Honeywell and Northrop Grumman as part of its nine-member general industry peer company list. However, Exelon’s net income of $3 billion is more comparable to that of these companies. CMS Energy’s performance peer group, as a counter-example, is composed of publicly traded utilities in the S&P 500 and S&P Midcap 400 indexes.

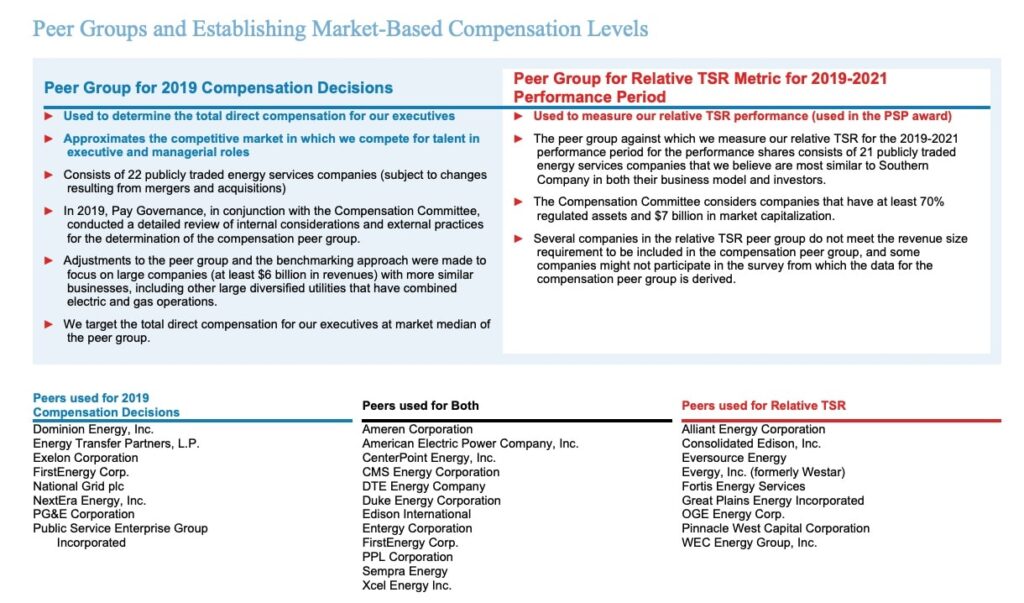

Southern Company is inconsistent in its selection of peer companies. The company used two different groups to assess its total direct executive compensation and relative TSR for the 2019 to 2021 performance period. While there was some overlap between the peer groups, the group Southern used to determine its total direct compensation consisted of 22 large energy service companies, “with more similar businesses,” while the group it used to determine its relative TSR consisted of 21 companies, including several considerably smaller corporations. Both of these choices could work to the benefit of the utility’s executives. Southern’s use of a group of larger diversified corporations to determine direct compensation could put upward pressure on its executive pay. Likewise, including smaller regulated companies in its TSR peer group could establish a more easily attainable TSR benchmark; relative TSR is a key metric in determining Southern’s long-term executive incentives.

These diverging benchmarks for assessing the varying portions of executive compensation can skew payouts in the utility executives’ favor. As Pozen and Kothari put it, “To provide a fair comparison, the peer group should consist of companies with similar revenues and market capitalizations and from similar industries. A biased peer group totally undermines its utility in setting compensation.”

Lavish Perks and Benefits

Private jets, personal legal and financial services, hospitality suites, premier health club memberships, sporting events tickets: these are just a few of the benefits utility executives enjoy in the name of “shareholder value creation and executive retention”, as disclosed in their financial reporting. Utility disclosures refer to these benefits by a variety of names, including “personal benefits,” “supplemental compensation,” and “perquisites,” more commonly referred to as “perks.” From traditional corporate extras such as access to company vehicles, to more unique line items like home security monitoring and genetic testing, these benefits pad utility executives’ already inflated compensation packages.

Many utilities attempt to characterize the cost of executive perks as so low as to be inconsequential. NextEra Energy terms its executive perks an “incremental” cost, outweighed by the benefits of increased productivity by its named executive officers (NEOs). PSEG states that “No NEO [named executive officer] received a perquisite in 2019 that exceeded the greater of $25,000 or 10% of the NEO’s total perquisite and personal benefit amount.” That is to say, $25,000 is not the total cap on all perks received by each PSEG executive, but simply the limit of any single perk.

While it may be true that the monetary value of these benefits is relatively low in the context of utility balance sheets, NEO benefits packages alone are worth more than the salaries of many non-executive employees, effectively widening company pay ratios in ways that are not clearly documented. Utility reporting varies widely in the level of detail provided about these benefits.

Premier executive transportation includes private aircraft, personal drivers

Executive use of private company aircraft is a common benefit offered by at least 14 of the 19 utilities covered in this report. Some utilities permit executives – and even their families and friends – unlimited personal travel on their companies’ private jets. Dominion Energy states that its Board has “directed” CEO Thomas F. Farrell, II to use corporate aircraft for personal travel for “security reasons,” and that family and guests may join him. Farrell’s personal use of Dominion aircraft amounted to $134,660 in 2019.

Southern Company CEO Thomas A. Fanning racked up a bill of $127,372 for personal use of the company aircraft in 2019. Similar to Dominion, the utility claims that the use of company aircraft allows NEOs to “perform their duties in a safe, secure environment and promotes safe and effective use of their time.”

Exelon CEO Christopher Crane received a value of $94,049 for personal use of corporate aircraft in 2019, plus $60,955 for spousal travel. Exelon Executive Vice President and Chief Strategy Officer William Von Hoene received a value of $119,917 for personal use of corporate aircraft, which the company said was largely related to commuting between Chicago and Washington D.C. Von Hoene also received a value of $15,459 for spousal travel.

FirstEnergy allows for “limited” personal use of corporate aircraft by executives and Board members, valued at $59,308 in 2019 for CEO Charles E. Jones. In 2017, Ohio state representative Larry Householder flew to Donald Trump’s presidential inauguration on board FirstEnergy’s corporate plane. “The trip marked a new period of cooperation between Householder and FirstEnergy Corp. as they worked to save the company’s struggling coal and nuclear plants in Ohio and Pennsylvania,” E&E News later reported.

Three years later, Householder would be removed as speaker of the Ohio House of Representatives and indicted on federal racketeering charges. Federal investigators allege Householder and several other defendants secretly used $60 million from FirstEnergy to elect Householder as speaker, and then enact a $1 billion bailout that allowed a bankrupt subsidiary of the utility to cancel plans to deactivate two nuclear plants and a coal plant.

Some utilities do require the repayment of any marginal costs incurred from personal use of corporate planes, while the companies generally foot the bill for the ownership and operation of the aircraft themselves. For example, NextEra stipulates that NEOs must pay the company for any non-business use based on the rate prescribed by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) for valuing non-commercial flights.

American Electric Power (AEP) CEO Nicholas Akins is not charged for fixed costs, such as depreciation and pilot salaries, associated with using company aircraft for personal trips, because the “aircraft are predominantly used for business use.” Akins does reimburse the company for some costs: “The incremental costs incurred in connection with personal flights for which Mr. Akins fully reimbursed the Company under the Aircraft Timesharing Agreement include fuel, oil, hangar costs, crew travel expenses, catering, landing fees and other incremental airport fees.”

Even in the case of business-related travel, some utilities allow NEOs’ spouses and even other guests to accompany them aboard company aircraft. WEC Energy’s policy explains that “the airplane cost is the same regardless of whether or not an executive’s spouse travels.”

Providing utility executives with company vehicles, leasing programs, and “automobile stipends” is also common. At least Con Edison, DTE, and PSEG foot the bill for the cost of a personal driver for their CEOs. NextEra spent over $130,000 on NEO vehicle expenses in 2019. Many utilities’ vehicle programs cover all associated costs, such as insurance, fuel, parking and maintenance.

Utility executives commonly receive gifts, charitable matching, and professional and lifestyle perks

Utility financial reporting includes several mentions of “gifts” for NEOs. Companies may present these to executives directly, such as with Exelon and Southern Company. In other cases, NEOs receive “sponsored” gifts, as in the case of AEP, which has explained that “executive officers may receive customary gifts from third parties that sponsor events.”

Some utilities, such as Alliant, AEP, Duke Energy, and FirstEnergy, also offer charitable gift matching programs, allowing NEOs to increase their own donations to charities at no additional personal cost. The Energy and Policy Institute has documented how utilities and their executives make charitable contributions to non-profit organizations that then go on to support the utilities’ political agenda, or that have ties to key policymakers.

Many utility executive benefits packages also include complementary professional services. Legal and financial counsel, plus tax planning and preparation are the most common. Details on the services provided to the executives are sparse. For Ameren, for example, neither the 2019 nor the 2020 proxy filing details the total expense of these perks, whereas Ameren discloses compensating CEO Warner L. Baxter with a value of $10,000 for tax and financial planning services in 2016 and 2017, respectively.

Most utilities’ executives are also feted with a wide range of “lifestyle perks,” described as ways to improve their quality of life, corporate retention, and NEOs’ overall performance and contribution to their companies. These benefits include things like health club and hospitality memberships (at least PSEG, NextEra, Dominion, and Ameren), home security systems (including PSEG, NextEra, Alliant, and DTE), and even genetic testing (for example, PPL). Dominion outlines “an allowance of up to $9,500 a year to be used for health club memberships and wellness programs, comprehensive executive officer physical exams and financial and estate planning” and Alliant reported spending nearly $30,000 on home security for CEO John O. Larson in 2019. There is little additional detail provided about many of these lifestyle benefits or their value.

Executives take home ample severance and non-qualified retirement benefits

Although utility executive perks are provided in the name of retention, they can also include additional retirement funds, generous predetermined severance packages, and, in the case of Arizona Public Service Company (APS), a consulting agreement worth nearly $2 million upon CEO Donald E. Brandt’s retirement. In 2019, APS paid Brandt, who retired that year, a $4 million “performance award” that in 2017 had been “designed to incent Mr. Brandt, a retirement-eligible CEO, to remain in his current role.” Upon his retirement, APS also awarded Brandt a “consulting services agreement” worth up to an additional $1.75 million.

In order to supplement executives’ 401(k)s and the associated contribution limits under the Internal Revenue Code, utilities commonly offer NEOs additional “non-qualified” retirement benefits. These plans go by a variety of names. For example, NextEra provides a Supplemental Executive Retirement Plan (SERP). As characterized in NextEra’s 2020 proxy statement:

“Current tax laws place various limits on the benefits payable under tax-qualified retirement plans, such as NextEra Energy’s defined benefit pension plan and 401(k) plan, including a limit on the amount of annual compensation that can be taken into account when applying the plans’ benefit formulas. Therefore, the retirement incomes provided to the NEOs by the qualified plans generally constitute a smaller percentage of final pay than is typically the case for other Company employees. In order to make up for this and maintain the market-competitiveness of NextEra Energy’s executive retirement benefits, NextEra Energy maintains an unfunded, non-qualified SERP for its executive officers, including the NEOs.“

APS, Ameren, Alliant, CMS Energy, DTE, Entergy, Eversource, PSEG, Southern Company, WEC, and Xcel Energy also offer SERPs. Xcel closed its program to new participants in 2008, with CEO Ben Fowke now the sole participant, while Entergy closed its program to new participants in 2014.

Similarly, Dominion offers NEOs two non-qualified retirement plans, including the Retirement Benefit Restoration Plan (BRP) and the frozen Executive Supplemental Retirement Plan (Frozen ESRP). Duke offers what it calls an Executive Cash Balance Plan (ECBP) and a Retirement Cash Balance Plan (RCBP). In addition to its SERP, Southern Company also provides a Supplemental Benefit Plan (SBP-P).

Outliers exist, though trend shows extra perks for utility executives remain the norm

Few of the utilities studied, including Xcel and CMS, have adopted a different approach to perks. According to its 2019 financial reporting, CMS Energy, for example, offers “No excessive perquisites. No planes, cars, clubs, security or financial planning.” Such decisions to limit extra benefits are an industry exception, however, rather than the norm.

Utility Profiles

Arizona Public Service Company (Pinnacle West)

Cover image source: “Monopoly Thimble” by Rich Brooks. Available in the public domain at Flickr.