Electric utilities falling behind on emission reduction targets

Many of the nation’s largest electric utilities are not on track to achieve their interim emission reduction goals or the “net-zero” targets they have communicated to customers and investors, according to industry data reviewed and analyzed by the Energy and Policy Institute. Progress is stalling at a critical juncture, as the Trump administration has targeted Clean Air Act rules and Biden-era grants for clean energy projects, and the utilities are projecting significant growth in electricity demand due to increased data center development. Some utilities are starting to back off some elements of their carbon goals, and recent data shows many utilities have slowed the pace in recent years. The utilities’ slowing progress should provide concern for lawmakers, customers, and investors interested in seeing the power sector continue its trend of decarbonization.

FirstEnergy announced in early 2024 that it abandoned its interim emissions goal in order to keep coal plants online.

American Electric Power (AEP) CEO Bill Fehrman said in November 2024 that the company may change its “aspirational” net-zero goal, pointing to the “red states” in which the utility operates as a reason for the possible abandonment: “It’s the state’s responsibility to decide what their policy’s going to be. And we’ll meet that policy.”

Duke Energy CFO Brian Savoy said it will consider delaying closure plans for all its coal plants after Trump’s presidential victory.

EPI examined 23 of the most carbon-polluting utility companies in the country. Almost all of the utilities EPI reviewed would need to accelerate the pace of their emissions reductions in order to reach their “net-zero goals.” We also found that 11 utilities have slowed down their pace in reducing emissions since 2017, when compared to the pace at which they have been decarbonizing since the respective baseline years that they used to set their emissions reduction targets. EPI examined data through 2023, the most recent available year of data reported by utilities that use a template provided by their trade association, the Edison Electric Institute.

EPI did not analyze utilities’ forecasts for how many gas plants they will build, how long they will operate them, and when they will retire their coal plants, which are some of the main questions driving the companies’ emissions trajectories. We compared the utility’s annual pace of reducing emissions to the necessary pace to achieve the targets that the utilities themselves set. Sierra Club’s October 2024 “Dirty Truth” report examined utilities’ coal retirement plans along with gas and renewable generation buildout and scored utilities based on their progress.

The new EPI analysis reconfirms what we first reported in 2019: the nation’s largest utilities planned to slow down their pace between 2020 and 2030, leaving the brunt of emissions reductions to 2030 through 2050. Data and sources are available at the hyperlinked Google sheet.

FirstEnergy abandons interim emissions reduction goal

FirstEnergy made headlines last year when the company announced during a February 2024 investor call that it removed the 30% by 2030 emission reduction goal that it set in 2020 in order to keep two of its West Virginia coal plants past 2030.

“We’ve identified several challenges to our ability to meet that interim goal, including resource adequacy concerns in the PJM region and state energy policy initiatives,” said CEO Brian Tierney. “Given these challenges, we have decided to remove our 2030 interim goal. Through regulatory filings in West Virginia, we have forecast the end of the useful life of Fort Martin in 2035 and for Harrison in 2040.” Tierney suggested to analysts on an investor call last month that the coal plants might stay online past 2035 and 2040. “We have about 3,000 megawatts of coal-fired generation that’s going to be retired — it’s planned to be retired, whether that happens or not, between 2035 and 2040,” said Tierney.

The utility’s 2030 emission reduction goal took into account only the utility’s “owned emissions” – also referred to as Scope 1 emissions by the utility – the pollution generated by the power plants that the company owns. Utilities report in varying levels of specificity whether their carbon reduction goals apply only to the power plants they own, or also to the emissions associated with the power that they purchase from third parties or wholesale markets and then distribute to customers. In 2023, FirstEnergy reported 14.9 million mt CO2e of owned emissions, and said that it needed to reach 12.4 million mt CO2e by 2030 to achieve that interim goal. However, as Tierney said, the utility forecasts it will not achieve the target.

Tierney did reconfirm the utility’s “aspirational” goal of achieving carbon neutrality by 2050. The utility reduced its owned emissions by 3.99% per year from its 2019 baseline to 2023, and can achieve the 2050 goal if it remains at that pace. This goal noticeably leaves out a significant amount of electricity that FirstEnergy purchases to supply its customers, and does not count those associated emissions as part of its goal, unlike some of the company’s peers.

FirstEnergy’s owned net generation (MWh) was reduced by 40% from 2018 to 2019 as a result of a bankruptcy process that saw creditors take control of its subsidiary, FirstEnergy Solutions, and create an independent company called Energy Harbor that owned the W.H. Sammis and Pleasants Power coal plants, along with other units. The utility said in its 2019 Climate Report, that it “will no longer be accountable for the emissions associated with three additional fossil fuel-fired generation facilities” when its former subsidiary FirstEnergy Solutions emerges from bankruptcy, “resulting in further reductions to FirstEnergy’s CO2 emissions.”

In other words, FirstEnergy counted its loss of several fossil fuel plants through the bankruptcy of its generation subsidiaries as contributing to its emission reductions goals even though the utility’s purchased power emissions increased by 57% from 2018 to 2019, and it did not absorb those emissions into its carbon accounting. While Duke Energy and Dominion Energy updated their net zero goals to include purchased power emissions, utilities like FirstEnergy that have goals that apply only to their owned power plants are leaving out large percentages of their overall carbon footprints.

Duke Energy rethinks the lifespan of its coal plants after Trump’s victory

Duke Energy’s pace in reducing emissions per year has slowed, but the utility appears to be on an approximate pace to achieve its 50% emission reduction goal by 2030 from a 2005 baseline. The path becomes more stark after 2030. Duke Energy must increase its pace to reach its 2040 interim target of an 80% reduction from a 2005 baseline. The 2030 and 2040 targets take into account only Duke’s owned emissions, while the 2050 net zero goal now includes the company’s purchased power emissions. The utility did not respond to EPI’s request for historical data of its purchased power emissions, which it does not report.

Duke Energy will have to reduce its owned and purchased emissions that totaled 88.8 million mt of CO2e in 2023 by 2050, and it has recently been telegraphing backsliding. The company noted in its 2024 CDP Corporate Questionnaire that its 2022 scenario forecast analysis “did not account for unprecedented load growth that is now being predicted.” Additionally, immediately after Trump’s presidential victory, Duke Energy CFO Brian Savoy said the company may consider changing its plans for its coal units, especially if Trump dismantles Environmental Protection Agency rules to reduce emissions from coal and gas plants. “The pace of the energy transition could change,” said Savoy.

The utility is hardly at the mercy of fate: it has urged that very dismantling.

On January 15, the utility co-signed a letter to Lee Zeldin, now the EPA Administrator, urging him and the Trump administration to “decline to defend” the regulations the agency has placed on greenhouse gas emissions from existing coal-fired and new gas-fired power plants. Duke Energy and the other utilities that signed the letter also requested a review of EPA’s rules to limit ozone pollution and wastewater discharges from power plants that typically include arsenic, lead, mercury, and other toxic metals.

In Ohio, Duke Energy opposes new legislation to repeal a ratepayer bailout of two coal-fired power plants. The bailout, which was enacted as part of the state’s bribery-tainted House Bill 6, is expected to cost Ohio customers of AES, AEP and Duke up to $1 billion by 2030.

The utility had already walked back coal plant retirement dates and is pursuing a large gas buildout, even absent any Trump administration actions. The utility’s Indiana subsidiary recently announced it will delay the retirement of its Gibson coal plant. Meanwhile, the company received approval from the North Carolina Utilities Commission to add 3.6 GW of gas over the next six years. These announcements could prompt investors and others to call into question the company’s ability to reduce emissions and hit its stated targets.

Slowing down and needing to significantly increase their pace to hit targets: Arizona Public Service, Entergy, NextEra Energy

The emission reduction paces of Pinnacle West’s Arizona Public Service, Entergy, and NextEra Energy have all slowed, according to the latest available data from the companies. Both Entergy and NextEra Energy each increased their actual emissions in 2023 compared to 2017, while APS’ pace has plateaued over the last seven years.

Both NextEra and APS are unique in the industry as they each have long-term goals to supply carbon-free electricity by 2050 – not just achieve carbon neutrality or be net zero.

APS has an “aspirational goal” of reaching 100% clean, carbon-free electricity by 2050 – announced in 2020 – two years after spending $37.9 million to help defeat a 2018 ballot initiative that would have required it to generate 50% of its power from renewable energy by 2030.

NextEra has a “Real Zero” goal by 2045, announced in 2022, which is a goal to eliminate all carbon emissions throughout its operations without the use of carbon offsets.

NextEra’s 2022 ESG report also reconfirmed its 2025 emission rate reduction goal. The utility aims to reduce its emissions rate – the emissions that it produces per MW of electricity it generates – by 70% by 2025 from a 2005 baseline. NextEra initially had set a 67% rate reduction goal by 2025 that it said “equates to a nearly 40% reduction in absolute CO2 emissions, despite the company’s total expected electricity production almost doubling over that time.” In other words, the utility said its goal would reduce its emissions by about 40% – from 45 million MT CO2 to approximately 29.5 million MT CO2 – by the end of 2025. The utility must make steep reductions in order to achieve that goal. NextEra did not respond to EPI’s questions about its 2025 interim target.

Entergy, which includes purchased electricity emissions as part of its net zero target, is in the midst of constructing large fossil gas plants. Entergy Mississippi began construction on the 754 MW Delta Blues Advanced Power Station in November, and the Louisiana utility is requesting approval from the Louisiana Public Service Commission to build 2.3 GW of fossil gas to serve Meta data centers. The utility also wants to build a $441 million gas plant to provide backup power for the grid serving Entergy Louisiana and Entergy New Orleans customers, along with its oil and gas customers at Port Fourchon.

Midwest utilities have made marginal progress, but will need to increase their pace

Alliant, Ameren, DTE Energy, Evergy, and WEC Energy have all cut emissions from their baseline year of 2005, likely a result of each utility shutting down coal plants. Alliant retired the Lansing Power Plant in Iowa. Ameren closed the Meramec Energy Center in Missouri. DTE shut down the River Rouge, Trenton Channel, and St. Clair coal plants in Michigan. WEC’s We Energies closed Pleasant Prairie in Wisconsin. Kansas City Power & Light, which became Evergy after its merger with Westar, closed the Montrose and Sibley coal plants.

But despite closing these coal plants, some of these Midwest utilities have delayed the retirements of other coal units and are currently pursuing fossil gas infrastructure.

Ameren is replacing Meramec with a 800MW gas plant. Alliant has delayed the retirement of the Edgewater Generating Station twice in the last few years, and the coal plant is set to be converted to a gas plant in 2028. The Columbia Energy Center coal-fired power plant, owned by Alliant, WEC’s Wisconsin Public Service, and Madison Gas & Electric, has also seen its retirement delayed twice by the utilities. It will remain open through 2029.

WEC has plans to convert the Oak Creek coal plant to a 1,100 MW gas plant – with units 7 and 8 being retired later this year – and to add 900 MW of more gas, according to the company’s latest investor relations presentation. The utility has targeted a 60% reduction in carbon dioxide emissions by 2025, from a 2005 baseline. Asked if the utility will achieve the target this year, a spokesperson said, “We have reduced our carbon emissions 56% compared to a 2005 baseline. We closed two coal units last year and we remain on target to meet our end of 2025 goal.”

Update: WEC’s We Energies announced on June 25, 2025 that it will keep units 7 and 8 at the Oak Creek coal plant online through the end of 2026.

Similarly, DTE also has a reduction target right around the corner – a 65% reduction by 2028 from a 2005 baseline, and an 85% reduction by 2032. The years coincide with the planned retirements of coal units at the Monroe Power Plant – half of the plant will retire in 2028 and a full retirement in 2032. Monroe is one of the largest sources of climate pollution in the country. When asked about the prospects of hitting the 2028 target, a DTE spokesperson said the company is on pace and pointed to its CleanVision Integrated Resource Plan (IRP) filing to Michigan regulators.

Evergy is also pursuing significant investments in fossil gas – the utility announced two 705MW gas plants for its Kansas service territory. The company also delayed its retirement of the Lawrence Energy Center, which burns coal, from the end of 2023 to 2028.

Update: Evergy removed the 2030 interim goal to reduce emissions 70% by 2030 from securities filings and from its sustainability website. The utility also delayed the retirement dates of units at the Lawrence Energy Center coal plant and Jeffrey Energy Center coal plant.

Xcel Energy has made progress but has slowed down and revised its emissions forecast upwards

Xcel Energy became the first major utility in the nation to announce a plan in 2018 to provide 100% carbon-free electricity to customers by 2050. The utility had begun to make significant progress in reducing emissions, partly due to legislation and shifting to a “steel for fuel” business approach that favored investing in renewable energy while retiring coal plants. For instance, Xcel ended operations at the Arapahoe Generating Station in 2013, retired the Black Dog coal-fired power plant in 2015, and completed the conversion of the Cherokee Generation Station to a gas plant in 2017. But recently the utility’s emission reduction pace has plateaued.

Xcel also had made a dramatic upward revision to its 2025 emission forecast in recent years. In 2022, the utility forecasted its 2025 emissions to be 25.4 million MT of CO2e. By 2024, it had increased the estimates by 37% to 34.9 million MT of CO2e for 2025.

Investors and other stakeholders may see Xcel’s reported emissions decline when 2024 data is released, since one of three units at the Sherburne County Generating Plant, or Sherco, was retired last year. Xcel initially tried to convert Sherco to a gas plant and even attempted to bypass regulatory approval after state utility regulators said it was premature to begin constructing a baseload gas plant. But Xcel has since admitted that the gas plant conversion does not make sense and instead is moving forward with a solar and storage plan – 710 MW of solar and a 10 MW/1,000 megawatt-hour battery system will be constructed near the plant.

Still, the utility has only a few years remaining to cut its emissions more than half to achieve its 2030 target, and will therefore need to ramp up its current reduction pace to do so, while also dealing with data center-fueled demand growth that it has pitched to investors as a load driver. Some signs suggest cuts in the near future. The Minnesota Public Utilities Commission recently unanimously approved an IRP settlement that puts the company’s Minnesota subsidiary on a path to eliminating coal and getting 63% of its energy generation from renewable energy by 2040 as the remaining units at Sherco and the Allen S. King coal plants retire by 2030.

Dominion and AEP are on track to hit 2030 target, but their goals don’t tell the whole story

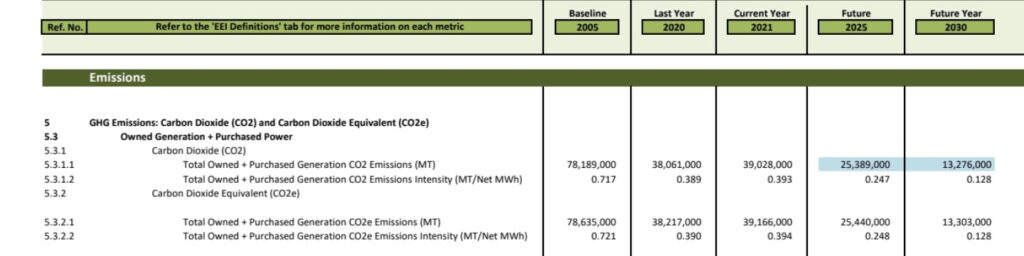

Emission data reported by American Electric Power and Dominion Energy show how the utilities are currently on a trajectory to achieve their respective 2030 interim reduction targets. AEP has an 80% reduction goal by 2030 from a 2005 baseline and Dominion’s 2030 target is a 55% reduction from 2005 emission levels. Similar to FirstEnergy, the utilities’ 2030 goals only account for their owned emissions – and both are purchasing power to serve customers that considerably drives up its emissions.

AEP updated its net zero goal to a 2045 target from its previous 2050 goal, but continues to exclude its purchased power emissions from its targets, unlike Dominion Energy when it broadened its net zero goal in 2022. With purchased electricity emissions taken into account, Dominion will need to increase its current 3% annual pace in reducing emissions to 3.7%. And Dominion will have to do that while it faces what it says is exceptional load growth. The utility projected a 376% increase in data center demand by 2038 last year for its Virginia service territory, and is moving ahead with plans to build a gas plant at the former site of the coal-fired Chesterfield Power Station. Chesterfield NAACP President Nicole Martin said that, “Dominion’s decision-making thus far has taken place in back rooms with little to no input from community members that will have to live with pollution from this facility every day.”

Dominion’s South Carolina subsidiary also recently received approval from state regulators of its integrated resource plan. The plan delays coal retirement dates for the Williams and Wateree plants and paves the way for a 2 GW gas plant – larger than the 1.3GW resource approved in Dominion’s 2023 IRP in the state.

AEP, meanwhile, can achieve its 2030 target if it remains at its current pace. However, that’s largely true because the utility has reported a significant increase in emissions associated with purchased power – and these emissions are not part of its goals. AEP reported 5.6 million MT of CO2e associated with the purchased electricity it made in 2021, compared to 34.9 million and 29.6 million MTs of CO2e in 2022 and 2023. In other words, 43% of AEP’s total emissions in 2023 – 69.3 million MT of CO2e – are from the electricity it purchased to serve customers. The utility did not respond to EPI’s request for comment about its purchased power emissions.

EPI previously revealed how AEP had undercounted its emissions associated with its ownership stake in an entity called the Ohio Valley Electric Corporation (OVEC) and its wholly owned subsidiary, Indiana-Kentucky Electric Corporation (IKEC). The units are owned by a consortium of utilities with AEP holding the largest equity stake. AEP ignored the emissions from these plants entirely in its 2019 emissions report to investors. One year later, AEP began counting the carbon emissions from the OVEC plants but categorized them under “purchased power,” which meant they would not be included under the company’s emissions reduction goals. An AEP spokesperson confirmed to EPI at the time of its 2020 report that its purchased power emissions in its 2020 report were derived from the OVEC plants. While AEP has now begun to detail purchased power emissions, it has conveniently set 2030 and 2045 goals to exclude these emissions.

Even without accounting for the nearly half of its pollution derived from purchased power, AEP appears to be showing early signs of abandoning its 2045 net zero. CEO Bill Fehrman told an audience at EEI’s Wall Street conference that the utility will effectively take its marching orders from states: “When 10 of our 11 states are red states, to go into those states and tell them we want to discontinue burning coal and natural gas because AEP has a carbon target, that isn’t well-received,” he said. “It’s the state’s responsibility to decide what their policy’s going to be … and we’ll meet that policy.”

Ferman reconfirmed the sentiment during the utility’s investor call in November: “If our states want renewables, we will work with them to deliver. If they want continued operation of coal or investment in gas or nuclear, we will work with them to deliver.”

In Ohio, AEP opposes new legislation to repeal a ratepayer bailout of two OVEC coal-fired power plants. The bailout, which was enacted as part of the state’s bribery-tainted House Bill 6, is expected to cost Ohio customers of AES, AEP and Duke up to $1 billion by 2030.

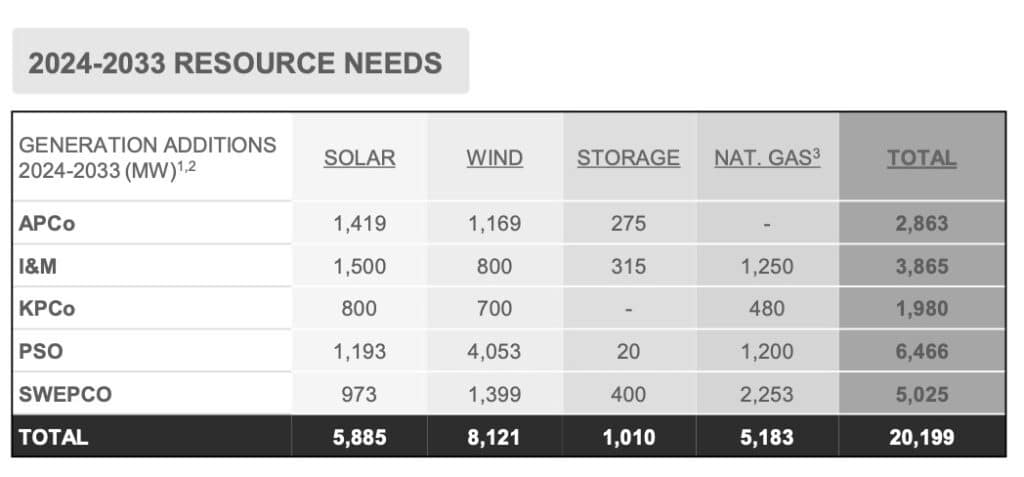

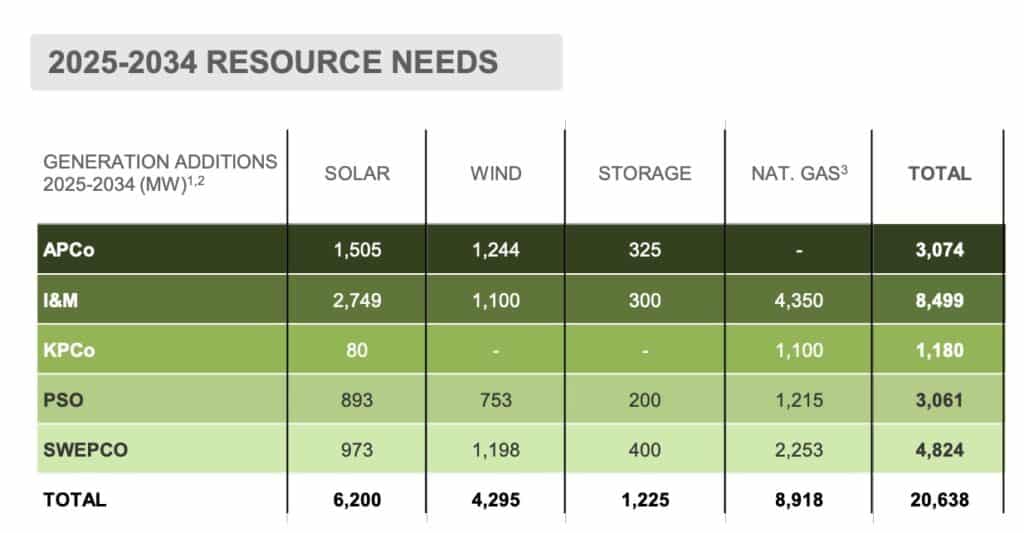

AEP also provided materials at an Edison Electric Institute financial conference, which occurred just days after Trump’s presidential victory, that detailed the utility’s future resource needs. Wind and gas resource forecasts were considerably different from the data presented in September at a Wolfe Utilities and a Barclays Energy-Power conference; wind energy projections decreased by 3.8GW and gas increased by 3.7GW.

Consumers Energy and NiSource: 15 years until their 2040 net zero targets

Consumers Energy and NiSource are the only investor-owned utilities with 2040, rather than 2050, net-zero goals, which puts them both in positions of having 15 years to reach their targets.

EPI’s previous reports in 2019 and 2020 noted how both utilities were going to achieve steep reductions in emissions by retiring their coal plants, foregoing the construction of new gas plants, and investing in renewable energy and battery storage. In the subsequent years, the utilities have planned some new fossil fuel investments.

Consumers Energy had an IRP approved in 2022 that secured the retirement of the J.H. Campbell coal-fired power plant in 2025 – 15 years earlier than previously planned. But the IRP also allowed the utility to move forward with the purchase of the 1,176-megawatt Covert gas plant that opened in 2004. Sierra Club sponsored expert testimony that criticized the utility’s modeling in the IRP process.

Nisource, the parent company of Northern Indiana Public Service Company (NIPSCO), announced a net zero by 2040 plan in 2022, but has received criticism for backsliding. NIPSCO has delayed the coal retirements of units at the Schahfer coal plant to 2025 from 2023, and recently received approval from state utility regulators to build a 400MW gas peaker plant.

Both utilities have highlighted the increase in load growth happening in their service territories to investors in recent presentations, but still confirmed their coal exit plans – Consumers Energy by 2025 and NIPSCO by 2028.

Large polluters still have a long way to go

Berkshire Hathaway Energy, Southern Company, the Tennessee Valley Authority, and Vistra remain as some of the largest emitters in the country. Vistra, TVA, and Berkshire have increased their pace in reducing emissions in the last few years – Berkshire in large part because it made minimal reductions last decade and has only recently started to retire coal units. Southern has slowed their pace.

Each of the four utilities has prioritized fossil gas plants or has delayed coal plant retirements.

EPI previously reported how Southern’s regulated electric subsidiaries have dismissed the company’s carbon goals as immaterial to their planning process. This sentiment appears to continue today. Southern’s subsidiaries in Mississippi and Georgia have each signaled they will seek to extend the life of three coal-fired power plants. The three plants, Plant Daniel in Mississippi and Plants Bowen and Scherer in Georgia, were slated for closure by 2028 (Daniel and Scherer) and 2035 (Bowen).

Southern Company’s 2030 goal – a 50% reduction of emissions from 2007 levels – was achieved in 2020, likely due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and then again in 2023 after emissions rebounded in 2021 and 2022. The utility stated in its 2020 Climate Disclosure report that it will achieve the goal five years early, and it has not accelerated an interim target in the meantime.

Berkshire Hathaway Energy, which operates a coal fleet that emits more nitrogen oxide gases than other coal-fired fleets in the country, according to an analysis by Reuters, will need to almost double its annual pace in reducing emissions in order to achieve its goal of a 50% reduction in emissions by 2030 from a 2005 baseline, along with its net zero by 2050 goal. Berkshire’s various subsidiaries are pursuing fossil fuel projects that might make achieving the goal difficult.

MidAmerican Energy, the company’s subsidiary in Iowa, has no plans to retire its five coal plants before 2049. An analysis by Synapse Energy found that the utility could save Iowans nearly $1.2 billion by retiring the units by 2030. MidAmerican also just filed plans to construct the Orient Energy Center – a 465 MW gas plant along with 800 MW of solar. PacifiCorp, which operates Pacific Power & Light and Rocky Mountain Power, filed an integrated resource plan in Utah that extends the life of its Hunter and Huntington coal plants beyond 2045. NV Energy’s North Valmy Generating Station, originally slated for closure, will now be converted to fossil gas. NV Energy also has proposed two additional gas peaking plants at North Valmy, which were not included in the company’s original proposal approved by the state’s public utility commission.

TVA’s net-zero plan received immediate criticism for being incompatible with its gas expansion plans. The utility is building more gas plants than any other utility in the country. The gas buildout does not appear to be stopping anytime soon – the utility released a draft of its IRP in 2024 that proposed anywhere from 4 to 19 GW of new methane gas plants. Democratic lawmakers urged TVA, a corporate agency of the federal government whose board is appointed by the President and confirmed by the U.S. Senate, to align its net zero plants with the then-Biden administration’s 2035 net zero goal. The lawmakers pointed to Winter Storm Elliot negatively impacting a number of TVA’s fossil units and the burden placed on communities by the utilities’ fossil plants:

“In addition to facing high energy burdens, families in the Tennessee Valley region suffer from the effects of TVA’s dirty energy mix, including exposure to the arsenic, chromium, lead, and mercury present in coal ash. In one recent case, TVA proceeded to dump coal ash in a predominantly Black neighborhood in South Memphis despite strong community opposition … Instead of relying on fossil fuels that unduly burden environmental justice communities, TVA should pursue clean, renewable sources of energy.”

Vistra had one of the fastest paces in 2023 for reducing emissions per year compared to its 2010 baseline – 3.85% – amongst its peers. The company has gone from emitting 173 million MT of CO2e to 86.3 million over those 13 years. In 2020, it accelerated its 2030 target to 60% from the original 50% reduction from a 2010 baseline, and it should achieve that target if it keeps its current annual reduction pace. However, like many of its peers, Vistra has delayed coal plant retirements. Vistra pushed the retirement date of the 1.1 GW Baldwin coal-fired plant in Illinois to 2027. Vistra was also one of the few utility co-signers of a January letter to Lee Zeldin, now the EPA Administrator, that urged him and the Trump administration to “decline to defend” the regulations the agency has placed on greenhouse gas emissions from existing coal-fired and new gas-fired power plants. Vistra joined Duke Energy and other utilities in pushing EPA to review its rules to limit ozone pollution and wastewater discharges from power plants that typically include arsenic, lead, mercury, and other toxic metals.

Methodology

In 2019 and 2020, the Energy and Policy Institute examined the emissions reduction and net-zero goals of the utilities with the highest carbon emissions according to rankings at the time compiled by MJ Bradley and Associates. The rankings drew from data that the utilities are required to report to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. For this report, EPI examined the same list of utilities from our previous reports. NRG Energy, PSEG, PPL, and Oklahoma Gas & Electric are not discussed in this report, though EPI did record their emissions and emission reduction rates. See all the data in this hyperlinked Google sheet.

Note: NRG Energy significantly reduced its emissions in recent years and achieved its 50% reduction by 2025 goal in 2023 compared to its 2014 baseline emissions. The utility, which is an independent power producer, has sold or retired assets in the last decade as it shifted away from owning one of the largest generation fleets in the country to become the energy retail provider it is today.

While EPI used the MJ Bradley database to determine the list of top emitting utilities for its earlier reports, we continue to source the data for all the utilities’ past and current emissions directly from the utilities’ own reporting, primarily from the companies’ use of an ESG reporting template provided by the Edison Electric Institute.

To determine whether the selected utilities were on a pathway to meet their own emissions reduction targets, EPI calculated each utility’s percent reduction per year from its baseline recorded emissions to its 2017 reported emissions, and its percent reduction per year from its baseline recorded emissions to its 2023 reported emissions (the most recently recorded emissions for utilities). EPI subtracted the baseline to 2017 percent from the baseline to 2023 percent to determine whether the utility had sped up or slowed down its emissions reductions pace. EPI then used the same calculation for utilities’ projected emissions based on their interim and/or net zero targets. EPI determined whether a utility must increase its pace to reduce emissions based on whether its percent reduction between its baseline year recorded emissions to 2023 was higher or lower than the percent change required annually to reach its interim or net zero targets.

Owned vs. Purchased Power Footprints

Utilities vary in whether their emissions reduction targets apply only to the power plants they own, or additionally include the emissions associated with the power they purchase from third parties or wholesale markets before selling it to customers.

EPI assessed emissions data based on whether an individual utility included only owned power, or owned and purchased power, in its emissions reduction targets. In some cases, a utility only includes owned power in an interim target and includes owned and purchased in its long-term net zero target. In these cases, EPI included that data in its analysis.

For some utilities, a significant percentage of emissions in some years derived from power purchases, but the companies’ targets only apply to their own power plants. That means that the companies’ goals are leaving out large percentages of their overall carbon footprints.

Because EPI’s analysis focused on the emissions that companies indicated are covered by their decarbonization targets, and from data reported by the companies to investors, the emissions data may differ from similar datasets.

What’s not in the data?

The data EPI analyzed do not include upstream emissions like methane leaks that occur from fracking or gas transmission en route to natural gas burning power plants, unless utilities accounted for that leakage in their self-reported data.

The data in this report does not include greenhouse gas footprints from gas distribution companies that are subsidiaries of the utility companies. Many of the utilities in this dataset own significant gas utility operations and are not reporting the carbon emissions related to their customers’ use of gas.