Many U.S. electric utilities plan slow decarbonization over next decade, out of sync with Biden plan

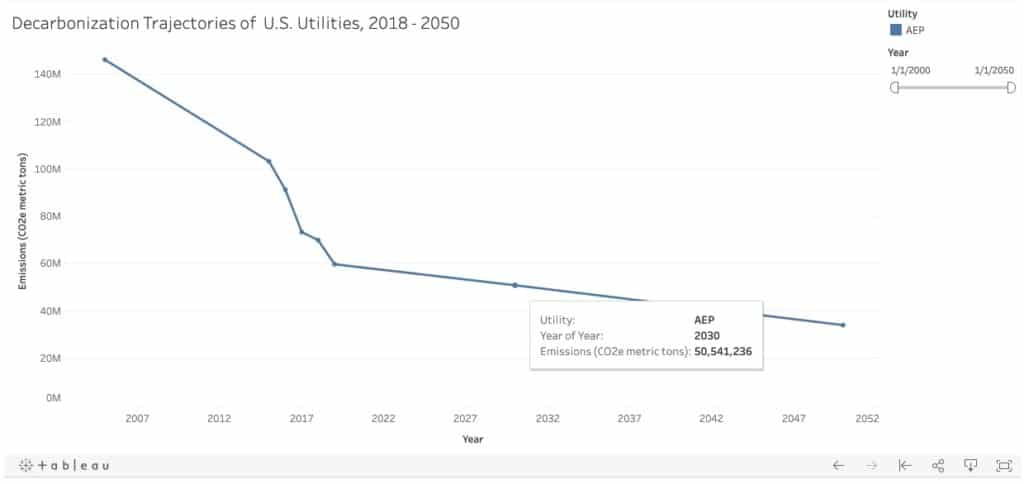

The country’s top emitting utilities are on decarbonization pathways that are too slow to meet the climate goals set forth by President-Elect Joseph Biden.

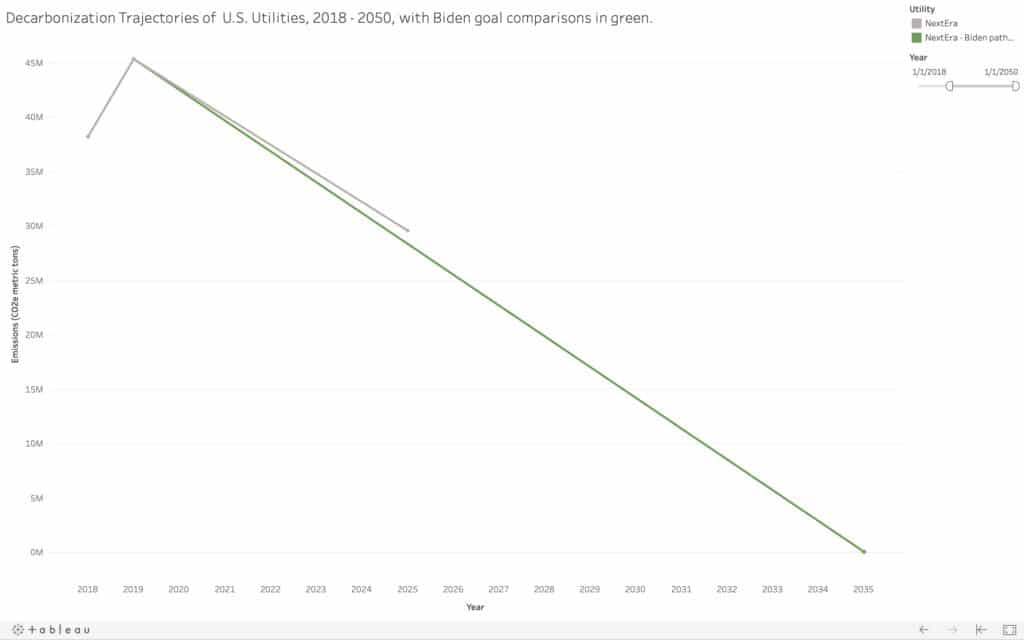

Biden has promised to achieve a zero-carbon power sector by 2035 en route to reaching an economy-wide target of net-zero emissions by 2050. Most of the country’s largest investor-owned utilities are on trajectories to phase out their use of coal and gas far too slowly to meet that 2035 target, according to an analysis of utilities’ decarbonization goals by the Energy and Policy Institute.

Major utilities and their trade associations have spent decades lobbying against state and federal climate policy and promoting denial and disinformation campaigns. During the Trump Administration, the utility trade association Edison Electric Institute – as well as individual utilities like American Electric Power (AEP), Duke Energy and FirstEnergy – supported the president’s effort to roll back regulations aimed at reducing carbon emissions.

But utilities also faced significant new pressure from investors and customers to embrace decarbonization, in addition to rapidly changing economics that favored clean energy, and almost all investor-owned utilities have attempted to show that they are responding to the new dynamics. In 2019 and 2020, most of the country’s top emitting utilities coalesced to set goals of reducing their carbon pollution to “net-zero” by 2050.

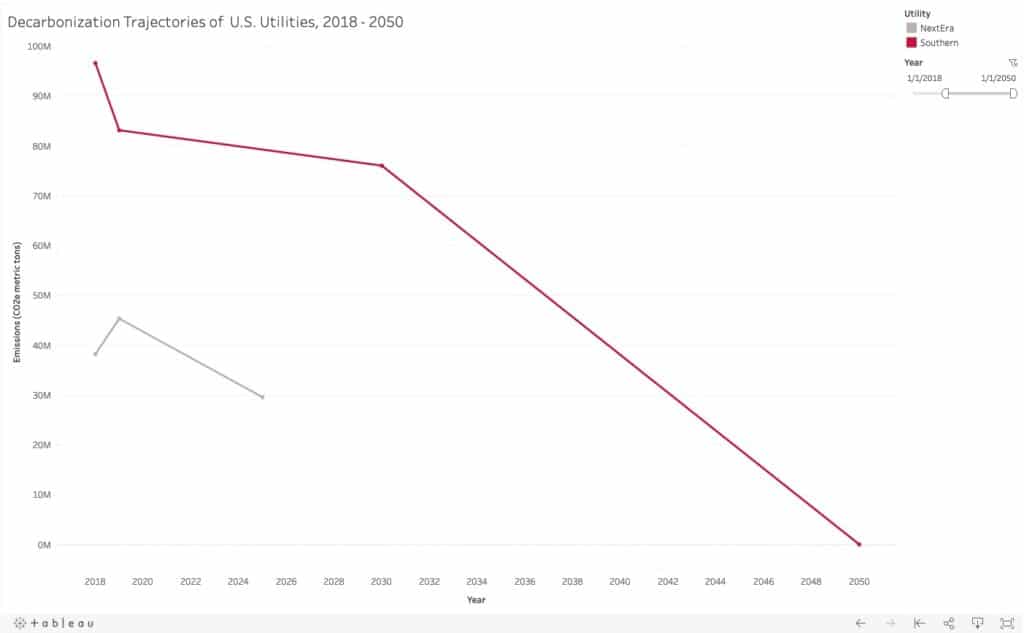

Beneath utilities’ “net-zero” framing and the consensus target date of 2050, however, the actual trajectories at which the utilities are promising to decarbonize – the shapes and slopes of their reduction curves – vary considerably, according to an updated analysis of the targets by the Energy and Policy Institute. The degree to which the utilities are relying on carbon offsets and accounting tricks and loopholes also varies widely.

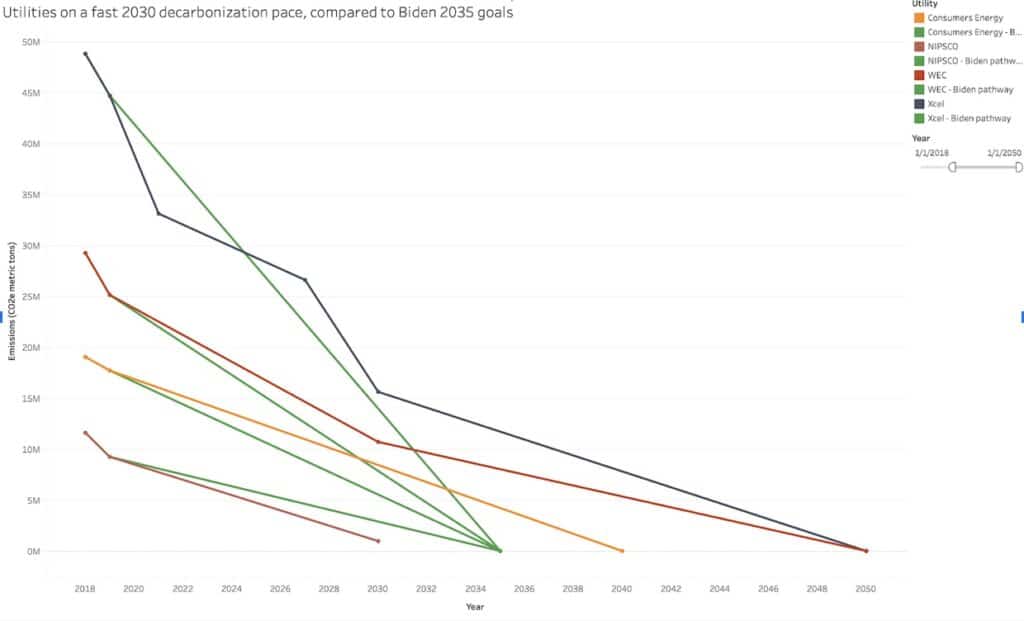

A few large utilities, predominantly in the Upper Midwest and the West, are pursuing emissions reductions at a rapid enough pace that they could conceivably hit the Biden target of net-zero emissions by 2035, or are at least putting themselves in position to be within the ballpark.

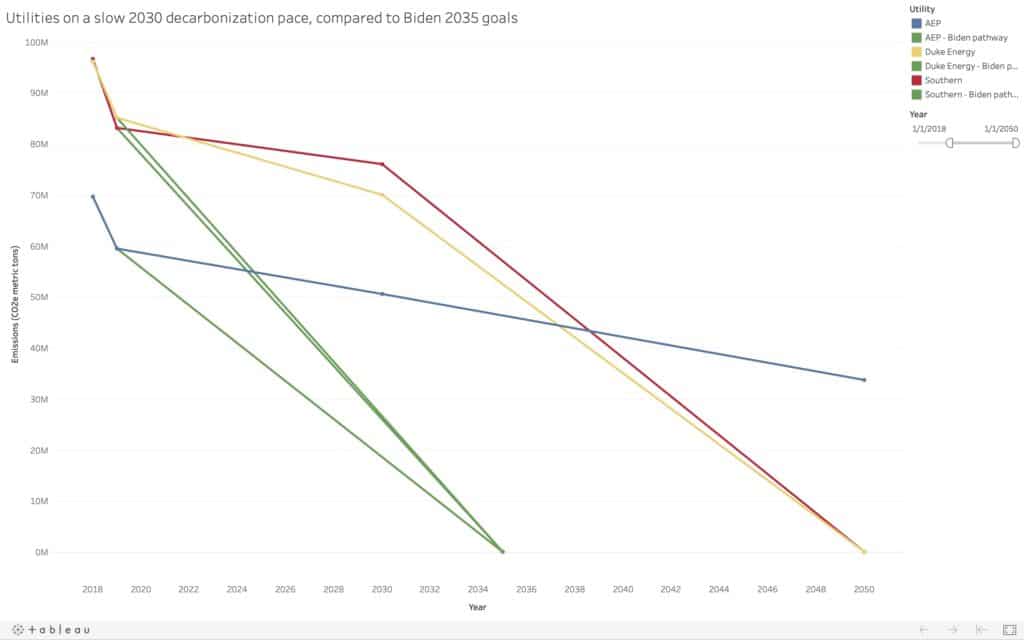

But other utilities – and particularly some of the country’s largest polluters, like AEP, Duke Energy and Southern Company – have set pathways to decarbonize at a slow rate during the crucial next decade, and are planning to speed up only after 2030. Those pathways are incompatible with the Biden goal, setting up a potential clash with the Administration that might challenge the green image the utilities have been attempting to cultivate in recent years.

Many of those same slow-moving utilities have not yet aligned their actual business plans with their decarbonization pathways, as they continue sinking money into new gas plants and forestalling the retirement of largely uneconomic coal plants.

A recent report from Deloitte similarly found “significant gaps” between 22 utilites’ net-zero commitments and their respective fossil fuel retirements and additions. The report also detailed how the utilities need to considerably deploy more renewable energy and energy storage, to build transmission lines, and to harness demand response and distributed solar generation – which large utilities still often seek to curtail – toward their net-zero goals.

“The math doesn’t add up yet,” Deloitte wrote of the gaps.

EPI’s updated analysis further reveals how several utilities have used accounting tricks to keep emissions off their books, and notes how some utilities with net-zero carbon commitments continue to allow some of their operating subsidiaries to ignore the parent companies’ decarbonization goal entirely.

Graphs illustrating the utilities’ decarbonization trajectories, along with comparisons to trajectories that would be necessary to meet the Biden 2035 goal, are here. The underlying data behind this analysis is available here.

Most large utilities pursue slow decarbonization rate between now and 2030

When EPI first assessed utilities’ decarbonization pathways in 2019, we found that most utilities were planning to leave the brunt of their emissions reductions to the 2030 – 2050 period, accelerating only after a relatively slow decarbonization effort during the 2020s.

Another year of data, and a new wave of utility commitments, shows that – with some important exceptions – that general trend of leaving the fastest reductions to the latter part of this half-century continues.

The consequences of the delay is not just the fact that ensuing CEOs will have to cut tens of millions of tons of carbon dioxide in a short period of time, but also that the emissions that could have been prevented between now and 2030 will remain in the atmosphere for hundreds of years. When combined with inaction from other fossil fuel companies, those differences could equate to extreme heat and sea level rise for hundreds of millions more people than if utilities decarbonized faster.

The actions that electric utilities take over the next decade are critically important. The Paris Agreement calls for limiting warming to “well below 2 degrees Celsius” with a further goal of 1.5° Celsius. The latest report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) recommends that all global carbon emissions be cut in half by 2030 to have a 50 percent chance of reaching the 1.5° scenario.

Those emissions reductions hinge on the rapid decarbonization of electricity, so that other polluting industries, such as transportation and commercial heating and cooling, can switch from burning fossil fuels to carbon-free electricity.

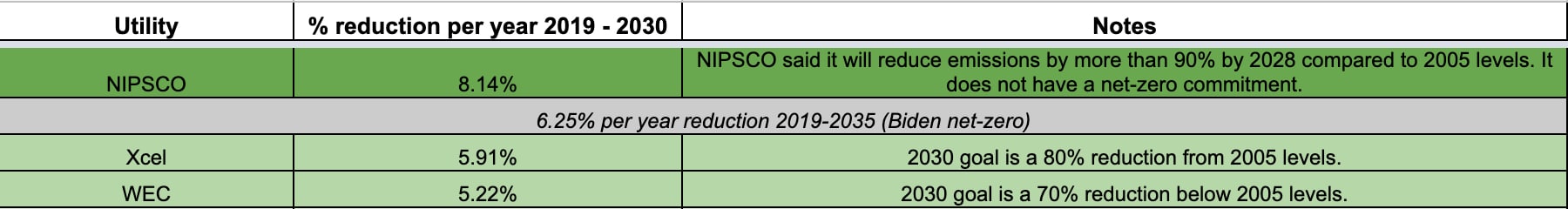

A few U.S. utilities have set ambitious 2030 goals. The Northern Indiana Public Service Co. (NIPSCO) plans to reduce its carbon emissions by over 90% by 2028, from a 2005 baseline. That reduction trajectory would equate to an average annual cut in NIPSCO’s carbon emissions of 8.14% from 2019, the most recent year with available data, and 2030, according to EPI’s analysis of its emissions data.

NIPSCO has said that it will achieve its steep reductions by retiring its coal plants, foregoing the construction of new gas plants, and investing in renewable energy and battery storage. The company told Indiana regulators that of all the pathways it analyzed, retiring coal and skipping gas in favor of renewable energy was the one with the lowest cost to consumers.

That finding from NIPSCO comports with what experts are increasingly reporting: A study from the University of California, GridLab and Energy Innovation released earlier this year found that the U.S. can achieve 90% clean, carbon-free electricity nationwide by 2035, dependably, at no extra cost to consumers.

NIPSCO’s decarbonization rate to 2030 is faster than what would be required to meet Biden’s 2035 zero-carbon target, which equates to a 6.25% per year reduction.

When Xcel Energy became the first major investor-owned utility two years ago to commit to going carbon-free by 2050, it also set a goal to reduce carbon emissions 80% by 2030 from a 2005 baseline in the eight states it serves. The utility is currently on a pathway that would reduce carbon emissions by an average of 5.91% per year from 2019 through 2030, according to EPI’s analysis.

WEC Energy, which owns We Energies in Wisconsin, said this July that it would reduce its carbon footprint 70 percent below 2005 levels by 2030, in addition to committing to net carbon neutrality by 2050. That puts WEC on a pathway to reduce emissions by 5.22% per year by 2030, according to EPI’s analysis.

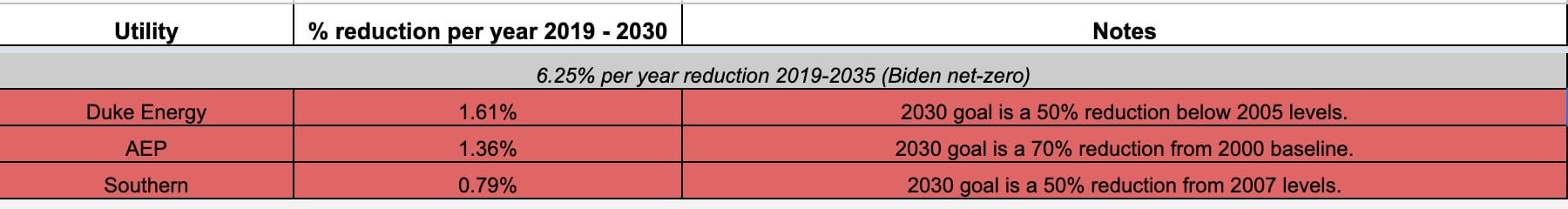

The country’s very largest utilities, however, continue to plan to decarbonize at a sluggish pace over the next decade.

Southern Company and Duke Energy were neck and neck leading the utility sector in carbon pollution in 2019.

From 2019 to 2030, Southern projects to reduce its carbon emissions by a meager 0.79% average annual reduction pace.

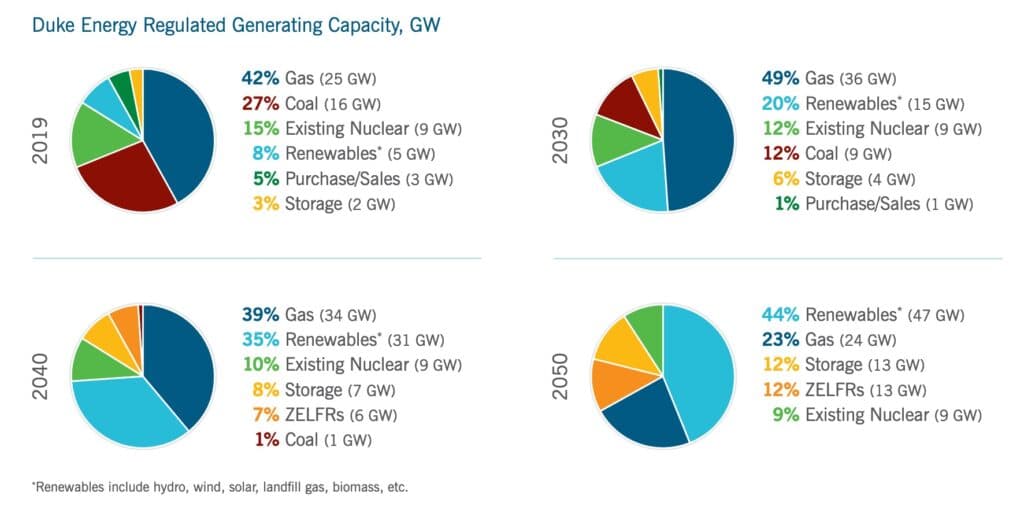

Duke Energy projects to reduce its carbon emissions over the same period by a 1.61% average annual reduction pace.

American Electric Power(AEP) emitted the fourth-most global warming pollution of U.S. utilities in 2019. From 2019 to 2030, it projects to reduce its carbon emissions by a 1.36% average annual reduction pace.

The majority of investor-owned utilities that EPI analyzed are more like Southern, Duke and AEP than NIPSCO; their decarbonization trajectories are far slower than Biden’s proposal would require.

Beyond NIPSCO, Xcel, WEC and Consumers Energy in Michigan (which has an annual decarbonization rate of 4.76% from 2019 to 2040, the date of its commitment) all other utilities that EPI assessed are intending to decarbonize at a pace that is less than half of what would be required to meet the incoming Biden Administration’s goal.

Not all net-zero commitments are identical

Beyond the varying decarbonization rates, another key distinction within the power sector is whether utilities are aiming to cease emitting any greenhouse gases by their target dates, or exploiting the “net” in their net-zero commitments to continue emitting while relying on other, often unspecified, carbon accounting schemes or offsets to negate that pollution.

Only a few utilities have promised to actually transition 100% of their electricity generation to sources that do not emit carbon.

APS and Xcel Energy have said that they intend to provide carbon-free electricity to their customers by 2050. APS serves more than 1.2 million customers in Arizona, and Xcel serves 3.6 million electric customers across eight Western and Midwestern states. Both utility CEOs have said they don’t know what technology their companies will utilize later this century to get the last remaining carbon emissions off of their grids, and they haven’t ruled out relying on carbon capture and sequestration technology that could keep fossil gas plants online beyond 2050, though APS has said that it expects “technological advances to eliminate the need to supplement renewable energy with even low-emitting carbon resources like natural gas.”

APS and Xcel have also set interim 2030 targets that signal to customers and investors the seriousness of their 2050 commitments. Xcel is aiming to cut its emissions by 80% by 2030 from its 2005 baseline. APS has not set a 2030 carbon reduction goal, but it says it will have an energy portfolio that is 65% carbon-free, 45% of which will be renewable, by 2030. APS says that it will also divest from coal no later than 2031.

Other utility leaders appear to have made net-zero commitments that will not require them to phase out all of their emissions, sometimes creating more questions than answers about their future business plans.

Southern Company, for instance, has left open the possibility of counting any avoided emissions caused by the electrification of other sectors, like transportation, toward its net-zero goal. Southern Company CEO Tom Fanning had previously floated transportation electrification as an opportunity for Southern to “take credit for” decarbonization. That accounting would belie the way that climate experts generally assume that “net-zero” goals would work for utilities, because limiting global warming to either 1.5°C or 2°C hinges not only on electrifying transportation, but also on powering that transportation with fully decarbonized electricity. (According to the IPCC, any 1.5°C or 2°C case requires all global electricity to reach zero carbon by 2050.)

Each of Southern Company’s regulated electric subsidiaries have also dismissed the company’s carbon goals as immaterial to their planning processes. In a Mississippi Power IRP meeting, the utility admitted under questioning about its share of Southern’s carbon reduction goals that, “Right now, there is no particular cap on Mississippi Power emissions and no particular requirement that we do anything other than maintain cost effective, reliable generation.”

Alabama Power said in December 2018, “We don’t have a share of that, per se. That is a Southern company enterprise-wide goal.”

When asked by the Georgia PSC staff how Southern Company’s goals affected Georgia Power’s IRP, the utility responded that the goals “did not influence the target amount of renewables proposed.”

Duke Energy’s recent climate report details a scenario in which the utility would source 23% of its generating capacity, or 23 gigawatts, from fossil gas in 2050, and to rely heavily on carbon offsets to be “net-zero.” Duke projects that its continued gas consumption under that scenario would emit 8 million tons of carbon dioxide that it would need to offset through tree planting or other “modified agricultural practices.”

Consumers Energy, a Michigan utility which aims to reach net-zero emissions in 2040, is decarbonizing faster than other utilities, but it has also said that it plans to rely on carbon offsets. Outgoing CEO Patti Poppe said that the utility “may offset further emissions through strategies such as carbon sequestration, landfill methane capture or large-scale tree planting.” The company’s 2019 energy plan made clear that its pathway to 2040 will result in a carbon dioxide emissions reduction of 90% from 2005 levels before offsets, which leaves about 2.5 million tons of carbon dioxide that it will cover with offsets.

Gas plant investments continue at some utilities, not at others

Many utilities are digging deeper carbon holes for themselves by continuing to invest in new gas-burning plants, which generally have expected lifetimes of 25 years or longer, taking them well past 2030 benchmarks and the Biden milepost of net-zero by 2035.

Duke, Southern, Entergy, DTE Energy, and Xcel Energy are all currently investing in gas plants or planning to spend customer dollars on building gas plants in the coming years.

Despite its relatively aggressive decarbonization goal compared to other utilities, Xcel plans to build a 786-megawatt gas plant in Becker, MN. The company is simultaneously lobbying Minnesota lawmakers to curtail community solar, according to a coalition of climate advocates in the state. Last year, Duke made known its plans to build 9,534 MW of gas capacity in the Carolinas alone. An updated integrated resource plan from Duke this September did include an option to forego gas, but the other plans Duke presented to North Carolina regulators all included heavy gas investments, ranging from 6,100 to 9,600 MW of new gas. Duke also has signaled the possibility of building 2,480 MW of new gas plants in Indiana.

Southern’s Alabama Power recently sought and gained approval to buy, build or contract for nearly 2,000 megawatts of gas resources. DTE Energy is expected to bring online a $1 billion, 1,150 megawatt gas plant in 2022.

Entergy CEO Leo Denault told investors in February the company planned to build as much as 4,000 megawatts of new gas by 2030.

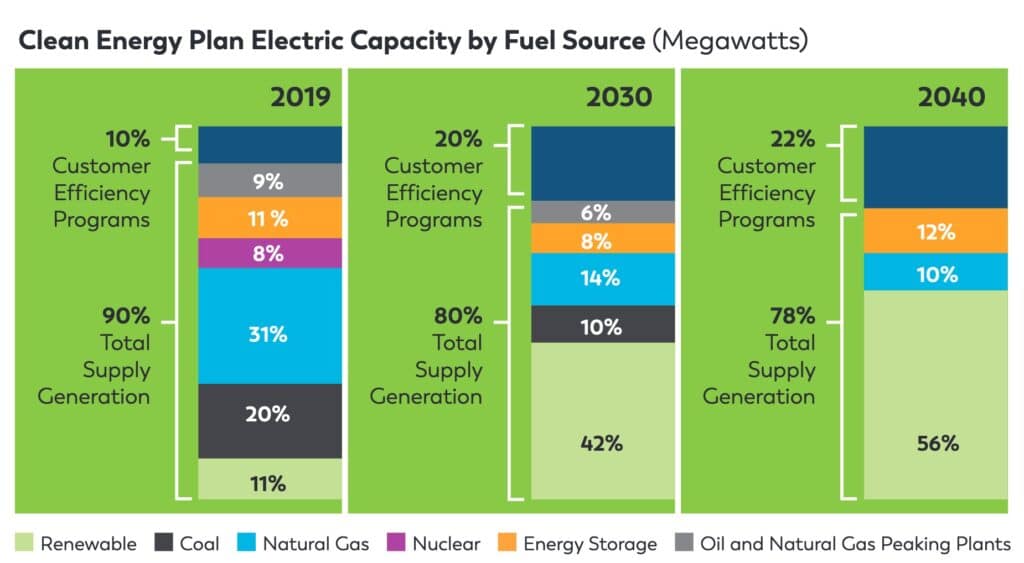

Other utilities have forsworn new gas investments. Consumers Energy has said that it will not build new gas plants. Consumers projects for existing gas to make up 13% of its capacity mix in 2040, with the remaining 87% coming from renewables and storage.

NIPSCO and PSEG have also said that they will not build new gas plants.

Coal on the decline, but utilities still set slow timelines for full phase-out

Coal has declined precipitously as a share of electric generation in the past decade, falling from over 45% in 2010 to 20% this year. Ratings agencies and financial analysts have estimated that coal’s share of generation will fall further to 8 to 10% by 2030.

Despite those general projections and utilities’ decarbonization goals, most utilities have either not stated specific dates by which they will be coal-free, or have set retirement dates for coal-fired power plants well past 2030.

Additionally, utilities are often running these plants at an enormous cost to their customers. A Union of Concerned Scientists report from this year found that regulated utilities in the Midwest alone overcharged their customers by at least $350 million in 2018 by selling them power from coal plants instead of from cheaper, cleaner resources.

Some utilities buck that trend: NIPSCO again leads the pack, with a projected coal-free date of 2028. NextEra and Entergy, each of which have relatively small remaining coal fleets, have said they will be coal-free by 2030 and 2031, respectively. Arizona Public Service has said that it will be coal-free by 2031.

But some of the largest consumers of coal in the country – again AEP, Duke Energy and Southern Company – have not set dates by which they will have stopped burning coal. Southern is one of the only utilities in the country seeking to increase its investments in coal. Its Mississippi Power subsidiary wants to install infrastructure to extend the lifetime of a coal plant there, Plant Daniel. NextEra, which co-owns the plant with Southern, wants to shut its share down.

Midwestern utilities DTE Energy, Consumers Energy, Alliant and Ameren have all set coal-free dates of 2040 or later.

| Utility | Year last coal plant will be retired |

|---|---|

| NIPSCO | 2028 |

| NextEra | 2030 |

| Pinnacle West (APS) | 2031 |

| Alliant | 2040 |

| Consumers Energy | 2040 |

| DTE Energy | 2040 |

| Emera | 2040 (Nova Scotia Power); 2023 (Tampa Electric) |

| Ameren | 2042 |

| Xcel | 2070 |

| AEP | No plans |

| Berkshire Hathaway Energy | No plans |

| Dominion | No plans |

| Duke Energy | No plans |

| Entergy | No plans* |

| Evergy | No plans |

| FirstEnergy | No plans |

| OGE | No plans |

| PPL | No plans |

| PSEG | No set date, but currently looking to sell fossil plants |

| Southern | No plans |

| TVA | No plans |

| Vistra | No plans for ERCOT coal plants |

| WEC Energy | No plans |

Deloitte found a similar dynamic. After describing the severe headwinds and risks facing coal-fired generation, the analysts noted, “Yet not all the [net-zero or carbon-neutral-committed utilities] have committed to a timeline for retiring all their coal capacity. While they have to various extents announced plans to eventually retire it, there is a large gap between current coal capacity and scheduled retirements over the next eight years.”

Utilities use accounting tricks to obscure emissions

Some utilities hold themselves accountable for purchased power emissions; most do not

Some utilities have also phrased their commitments in ways that abdicate their responsibility for reducing large tranches of emissions.

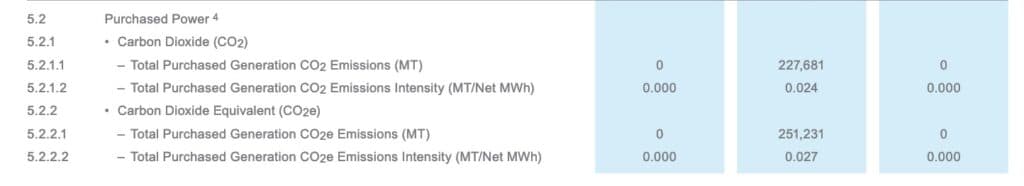

Most of the utilities that EPI assessed in this report have said that they will not be responsible for the emissions associated with power that they purchase from wholesale markets, or in bilateral contracts from power plants owned by other parties.

The differences can be significant. FirstEnergy’s carbon commitments cover only the emissions associated with the power plants it owns – a stance it reaffirmed in November when it said that it would reduce its carbon emissions by 30% by 2030 from a baseline of 2019.

That appears to leave out a large chunk of the emissions associated with the electricity that FirstEnergy sells to customers. According to data that FirstEnergy reports to investors, 38% of the emissions associated with FirstEnergy’s electricity sales in 2018 came from power that it purchased, which are not covered by the company’s goal.

Other utilities, including Duke, Dominion, Southern, AEP, Entergy, DTE, Ameren, PPL, Pinnacle West, OG&E, NIPSCO, TVA and Evergy also do not appear to count purchased power as covered by their emissions reduction goals, or are not clear about this accounting.

Xcel, NRG, WEC, PSEG, and Consumers Energy were clear in their reporting that their goals do cover the emissions associated with their purchased power.

AEP deceptively scrubs its emissions accounting of any equity in OVEC coal plants

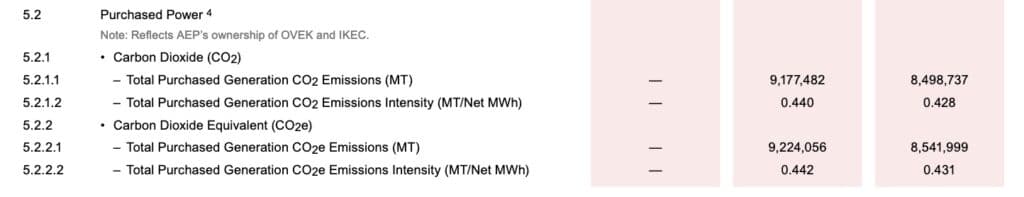

AEP’s undercounting of the emissions covered by its goal uses a further sleight of hand that might affect how investors view the integrity of its emissions commitments. AEP owns a 43.47% ownership stake in an entity called the Ohio Valley Electric Corporation (OVEC) and its wholly owned subsidiary, Indiana-Kentucky Electric Corporation (IKEC).

OVEC is owned by a consortium of utilities, with AEP holding the largest equity stake. It exists solely to operate two coal-fired power plants: the Clifty Creek plant in Indiana, and the Kyger Creek plant in Ohio, both built in the 1950s.

AEP ignored the emissions from these plants entirely in its 2019 emissions report to investors. In 2020, AEP began counting the carbon emissions from the OVEC plants but categorized them under “purchased power,” which meant they would not be included under the company’s emissions reduction goals. An AEP spokesperson confirmed to EPI in an email that the newly apparent purchased power emissions in its 2020 report were derived from the OVEC plants.

AEP’s relationship to these emissions is different from a utility’s relationship to emissions associated with power that it purchases from wholesale markets. AEP is by far the largest plurality equity stakeholder in OVEC – it has leverage over whether the plants continue to operate or retire.

The effect of excluding the plants from AEP’s carbon accounting is massive. AEP has a goal of reducing its emissions by 70% by 2030 from a baseline of 2000, which equates to a reduction of 9 million MT of CO2 equivalent (CO2e). (The company also says that it has an “aspirational” goal of having zero emissions in 2050, though it has not updated its 80% reduction goal of that year.)

AEP’s data indicates that it considers the power it purchased from OVEC – or, in effect, from itself – created 8.5 MT of CO2e in 2019. If AEP considered itself responsible for those OVEC emissions, its reduction task would be considerably tougher, and it would likely have almost no way to achieve its goal without shutting down or otherwise divesting itself from the two OVEC plants and their emissions.

That would be inconvenient, given that AEP has instead spent the last three years lobbying for more subsidies to help the plants, which are uneconomic after nearly 70 years in service, to remain in operation. Indiana also passed a bill benefiting OVEC this year.

The additional subsidies which AEP sought passed as part of HB 6, the Ohio legislation now at the center of federal corruption charges. AEP funded a 501(c)(4) dark-money group that contributed funding to Generation Now, the group at the center of the federal criminal complaint which charged the Ohio speaker of the House in a $61 million bribery scheme with the end goal of passing HB 6.

EPI has also reported how AEP was involved in a host of other efforts from 2017 onward to secure subsidies for the OVEC plants, including drafting legislation and dark-money spending. AEP made campaign contributions earlier this fall to seven Ohio state representatives after they joined a new select committee tasked with repealing and replacing House Bill 6.

The subsidies finally secured for the OVEC plants by HB 6 will charge up to $1.50 per month from Ohio’s electricity customers through 2030, with customer charges coming to about $450 million, according to the Energy News Network.

On its website, AEP notes: “Some stakeholders are asking AEP whether our lobbying practices and the policy positions taken by trade organizations to which we belong are in alignment with the Paris Climate Agreement. We believe in transparency and active participation in public policy development, regardless of the issue or position.”

FirstEnergy, PPL take carbon reduction credit for selling coal plants that keep operating under new ownership

FirstEnergy’s data would indicate to a casual observer that it dramatically reduced its carbon emissions from 2018 to 2019, by a full third. That reduction happened because FirstEnergy’s subsidiary that owned its merchant coal plants declared bankruptcy in 2018. It emerged as a separate company called EnergyHarbor this year. The coal plants continue to operate.

PPL similarly sold off all of its merchant coal fleet since 2010, and it accounts for those sold coal assets as part of its successful decarbonization. If the goal were just based on PPL’s current business, it would reflect a far more modest 45% reduction from 2010 levels to 2050, as PPL acknowledges (see p36).

Gas utilities’ net-zero commitments rely on the continued use of gas

Many investor-owned utility companies own gas distribution utilities, in addition to electric ones. These companies generally initially limited their decarbonization commitments to their electric utilities. But in the past year, they have also started to declare net-zero commitments for their gas subsidiaries as well.

Climate commitments are important for gas utilities not only because the gas that they sell emits carbon dioxide when burnt, but also because methane leaks occur throughout gas extraction, transmission and distribution systems.

Methane has a shorter atmospheric lifespan than carbon dioxide, but has a global warming potential that is 84 to 87 times greater. The latest UN IPCC report makes clear that economies must not only make deep reductions in carbon dioxide, but that they must also focus on short-lived pollutants like methane because of the need to make immediate cuts to maintain any hope of limiting warming to 1.5 degree celsius.

Methane emissions are on the rise and U.S. oil and gas drilling is a major contributor to the increase as utilities have expanded their gas demand.

Utility investors have started to express growing concern about the risks associated with utilities’ gas systems. As You Sow, a shareholder advocacy organization, recently said, “As investors, we don’t expect any natural gas utility to have all the answers now as to how it will evolve and thrive in a decarbonizing world that enables us to avoid the worst impacts of the climate catastrophe. We do expect gas utilities to recognize change is coming and to begin the hard work of questioning and planning for a new energy future.”

Likely in response to investors’ concern, DTE Energy and Dominion say they will achieve net-zero emissions in their gas businesses by 2050. Duke Energy recently said it will reduce emissions in its natural gas business to net-zero by 2030.

Like many electric utilities, the gas subsidiaries are primarily counting on offsetting the emissions from their leaked methane and from the combustion of the gas they sell through other means instead of actually decarbonizing their gas subsidiaries.

Most advocates for climate action have suggested that decarbonization of the direct use of gas would be best achieved by switching buildings and industries that burn gas to run on electricity, a process known as electrification. That change would be devastating for gas utilities’ business models, though it would provide growth opportunities for the electric utilities that are often owned by the same companies.

Gas utilities have rejected that approach. Instead, they argue that they would net their emissions to zero by replacing some of the fossil gas that they sell to customers with renewable natural gas (RNG), or biomethane that is captured from other human sources, generally landfills or agricultural waste. The gas utilities have also indicated they will also purchase offsets from forestry companies.

While biomethane or RNG may be useful in some applications for industries that would be difficult to electrify, it is currently extremely costly, and studies indicate that it would be difficult, if not impossible, for utilities to capture enough biomethane at scale to displace fossil gas. If they could do so, it would be more expensive than simply converting most customers to electricity. Beyond the climate problem, RNG also does not solve the indoor air pollution problems that researchers are increasingly uncovering as a consequence of burning gas in homes and buildings.

Despite those issues, gas utilities are using the promise of RNG as a cudgel to stave off electrification efforts with policymakers.

DTE Energy CEO Jerry Norcia told investors that he feels confident that RNG will appease ESG investor concern. During the 2020 second-quarter call with analysts, Norcia was asked about decarbonization trends within the gas sector. Norcia said the initiatives the company has in place “adds value to our investors.”

Norcia’s peers similarly believe they have positioned themselves to deal with concerns with methane emissions.

WEC Energy Chairman Gale Klappa said that the company’s pipeline replacement program, particularly in Chicago through the Peoples Gas subsidiary, is what executives discuss during ESG visits. Replacing pipelines can lower methane leakage rates, but it also locks in fossil fuel infrastructure for decades, risking never-ending pollution for communities and the climate, and stranded assets for investors.

While Xcel Energy has generally been perceived as a leader for the decarbonization efforts its electric utility is undertaking, it is far less enthusiastic about decarbonizing its gas utility via electrification, even if electrification could create business growth for its electric arms. CEO Ben Fowke has said the electrification technologies are “pretty tough to make work” in the Upper Midwest, and so Xcel will focus on RNG instead. Fowke also recently said the utility industry “needs to be more demanding” that the extraction companies supplying Xcel with gas reduce their methane emissions.

Gas utilities may also face headwinds from a Biden Administration. In addition to his goal of decarbonizing electricity by 2035, Biden has also set a target of halving the carbon footprint of the U.S. building stock by 2035 by “creating incentives for deep retrofits that combine appliance electrification, efficiency, and on-site clean power generation.” Biden’s climate plan also includes goals to “upgrade 4 million buildings and weatherize 2 million homes over 4 years … by funding direct cash rebates and low-cost financing to upgrade and electrify home appliances.”

A few utilities still do not have absolute emissions targets

Of the 22 investor-owned utilities that EPI assessed, only a few remain that have not set any reduction targets for their absolute emissions.

Berkshire Hathaway Energy, which owns NV Energy, MidAmerican Energy, and Pacificorp, has not set an emissions reduction goal. Berkshire’s utilities barely decreased emissions in recent years, moving from 68 million MT CO2e in 2017, to 71 million in 2018, to 67 million in 2019.

Unlike other utilities which have been pushed to decarbonize by ESG investors, Berkshire Hathaway Energy is itself a subsidiary of Berkshire Hathaway, the behemoth corporate conglomerate, and Warren Buffett personally controls over 30% of Berkshire Hathaway’s voting power, as reported by Greentech Media.

NextEra Energy recently surpassed Exxon as the largest company in the world by market capitalization. Because the company develops wind and solar farms, headlines described it as a clean energy company overtaking the fossil fuel giant, a sign of the times. But unlike its peers, NextEra has not set an absolute emissions reduction goal, drawing questions from investor analysts. NextEra instead says that it aims to reduce the amount of carbon it burns per unit of electricity it generates, or its carbon intensity, by 67% by 2025 from a 2005 baseline. The company estimates that this intensity reduction “equates to a nearly 40% reduction in absolute CO2 emissions” from the same baseline. That absolute reduction would equate to a reduction pace of 5.8% out to 2025, relatively fast compared to peers and fairly close to the pathway that would be required to meet Biden’s 2035 goal. NextEra does not have any emissions reduction goals for beyond 2025, however.

NextEra derived 62 percent of its net income in 2019 from its massive electric utilities in Florida: Florida Power & Light and Gulf Power, the latter of which NextEra acquired from Southern Company. While NextEra is planning to phase out Gulf’s coal consumption, which likely enables the fast reduction pace it has scheduled through 2025, the company has no such ambition when it comes to gas. Florida Power & Light and Gulf, combined, project to derive over 60% of their generation mix from gas in 2029, and continue to invest in new gas infrastructure.

Other companies have set goals conditional on policy changes. PSEG says its ability to attain net-zero carbon emissions is dependent on “customer behavior and public policy.” Evergy similarly has said it has the “potential” to reduce emissions 85% by 2030 compared to 2005 levels – far faster than its goal of an 80% reduction by 2050 – but that this pace will “ultimately be defined in collaboration with the Company’s stakeholders.” Evergy has been an advocate for policies in Kansas and Missouri to enable the securitization of its coal plants, which would allow the utility to use ratepayer-backed bonds to refinance and close uneconomic coal plants.

Methodology

The Energy and Policy Institute examined the carbon goals of the 22 investor-owned utilities with the highest carbon emissions, based on their estimated 2018 carbon emissions according to a ranking compiled by MJ Bradley and Associates, which draws from data that the companies are required to report to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

EPI also included TVA, a federally owned corporation, due to its size and public status. AES is an investor-owned utility that would have qualified under those criteria, but which EPI excluded from the data set since the majority of its electric generating capacity is from outside the U.S. EPI included two publicly-owned companies that primarily operate as independent power producers, Vistra and NRG, because they are top emitters and they have emissions reduction goals.

While EPI used the MJ Bradley database to determine the list of top emitting utilities, we sourced the data for all of the utilities’ past and current carbon emissions directly from the utilities’ own reporting, primarily from the companies’ use of a reporting template provided by the Edison Electric Institute.

For utilities that left holes in their reporting on the template, such as baseline year emission data, EPI used data either from the utility’s sustainability reports, or from their filings to CDP, a carbon disclosure organization. In a few cases, basic math was needed to fill in the data so that companies could be more easily compared to one another. For example, most companies use 2005 as a baseline year, in keeping with conventions of the Paris Agreement and President Obama’s Clean Power Plan. Southern Company set its baseline at 2007 and does not disclose its 2005 emissions data. It did, however, say that “Without federal mandates, total annual emissions in 2016 were approximately 27 percent lower than 2005 levels,” which EPI used to derive an estimate of its 2005 emissions.

Many companies had discrepancies in the data that they reported via their EEI/ESG template, compared to data they reported to investors in other venues. For instance, Southern Co. reported in the EEI template that its power plants emitted 83.1 million metric tons of CO2e in 2019, and 152 million metric tons in its baseline year of 2007. To CDP, it reported those numbers as 88.2 million and 157 million, respectively.

Owned vs. Purchased Power Footprints

Utilities report to varying levels of specificity whether their carbon reduction goals apply only to the power plants they own, or also to the power that they purchase from third parties or wholesale markets before selling it to customers.

Most utilities indicated that their goals applied only to the emissions from their own power plants. In those cases, EPI only assessed emissions data from the utilities’ owned power plants. For utilities that made clear that their goals also applied to emissions associated with their purchased power and reported those emissions, EPI included that data in its analysis.

For some utilities, a significant percentage of emissions in some years derived from power purchases, but the companies’ goals only applied to their owned power plants. That means that the companies’ goals are leaving out large percentages of their overall carbon footprints.

Because EPI’s analysis focused on the carbon emissions that companies indicated are covered by their decarbonization goals, and from data reported by the companies to investors, the emissions data may differ from other similar datasets.

What’s not in the data?

The data EPI analyzed do not include upstream emissions like methane leaks that occur from fracking or gas transmission en route to natural gas burning power plants.

The data in this report does not include greenhouse gas footprints from gas distribution companies that are subsidiaries of the utility companies. Many of the utilities in this dataset own significant gas utility operations and are not reporting the carbon emissions related to their customers’ use of gas. NIPSCO, for instance, has an ambitious plan to decarbonize its electric generation, but that plan does not cover the gas distribution subsidiaries that are also owned by NIPSCO’s parent company, NiSource.

Featured image: Kyger Creek Power Plant. Source: FunksBrother, Wikimedia.